Tiger attacks on humans and cattle have led to people around jungles in Banke and Bardiya stopping cattle rearing. As the people do not have other means of income, their livelihood is in crisis.

Mukesh Pokharel |CIJ, Nepal

Ram Bahadur KC. Photo: Mukesh Pokharel

Ram Bahadur KC, a resident of Madhuvan-3 in Bardiya, was sitting on his scaffold, looking over at his paddy fields, worried that elephants from the Bardiya National Park could destroy his paddy. At this moment, he heard the radio say the number of tigers in the country had more than doubled to 355 this year from 121 in 2009.

“How many more people will the tigers kill now?” said a dejected Ram Bahadur. When Ram Bahadur relayed the news to his wife, Durga, she became equally sad.

The Ministry of Forests and Environment on July 29 this year, on the occasion of the International Day of Tigers, declared Nepal’s unmatched feat in tiger conservation. The news was vociferously carried by major international media, including the National Geographic and the CNN, and conservation bodies including the International Union for Conservation of Nature and the World Wildlife Fund. Prominent Hollywood actor Leonardo Decaprio tweeted to celebrate the success.

However, Ram Bahadur’s family was not happy. And why would he? After all, his father, Chitra Bahadur, had been killed by a tiger on July 5 last year. Chitra Bahadur had gone to the jungle to collect fodder when he was attacked and injured. He succumbed to his injuries even before he was taken to a hospital.

The son, who had just finished the annual commemorative rites for his father, thus, had no fascination for the increase in tiger count. “We wouldn’t have a problem with the tigers if they didn’t come out of the national park. But they visit us right where we are collecting grass and firewood,” Ram Bahadur said.

According to the Bardiya office of the National Nature Conservation Trust, three wards (2, 3 and 5) of Madhuvan Municipality itself have seen the deaths of 8 people in tiger attacks in the one year between mid-May, 2020 and mid-May, 2022.

Even as the news of the increase in tiger count in Nepal excites many people globally, the families of the victims of tiger attacks and those living in near jungle areas live with fear.

Dhan Bahadur Adhikari, a resident of Ratnanagar-5, is also unhappy with the news about the increase in tiger count. Last year, his wife, who had gone to the jungle to collect fodder for their goats, was attacked and killed in a tiger attack. “We are even more scared as we live near the jungle,” said Adhikari, whose home is next to the Jankauli community forest.

According to Hari Gurung, Khata Community Forest Coordination Committee chairperson, even the villagers who had supported the conservation campaign were not happy. “The villagers have started asking what we got by saving tigers and why we should save them anymore,” Gurung said.

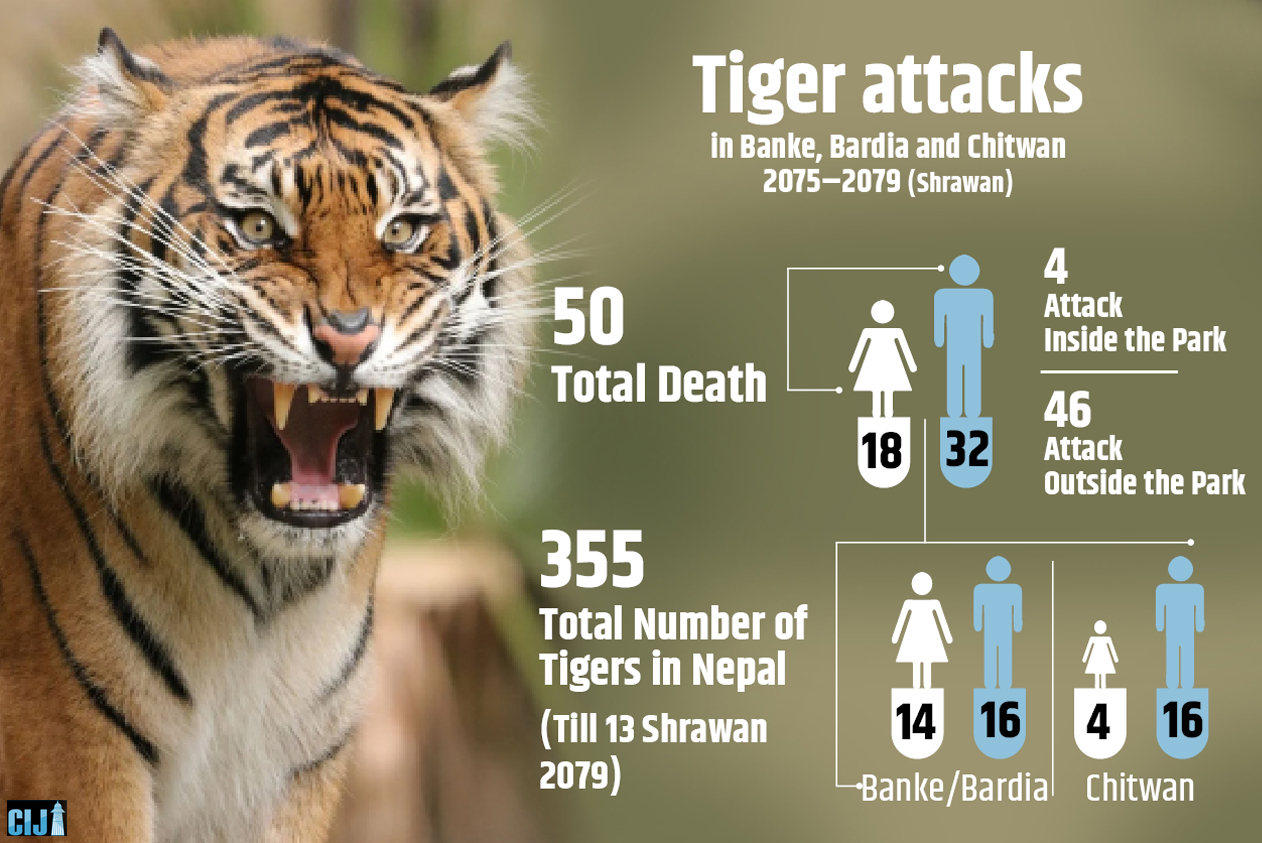

Fifty people have died in the four years between mid-April 2018 and mid-April 2022 in Chitwan, Banke, Bardiya. See infographics.

Cattle sheds are empty, and food is getting scarce

With the rise in the number of tiger attacks, villagers’ entry into the jungle has become infrequent. The villagers have not been able to rear cattle for there is less fodder and grazing area. Resultantly, the villagers have started facing problems in livelihood.

Until a couple of years ago, Dilkumari Rana Magar, a resident of Rapti Sonari-1 in Banke, had 80 cows and oxen, 16 buffaloes and 60 goats. She had hired three caretakers for the cattle. She earned Rs400,00 per year by selling milk, ghee and goats. However, her cattle sheds have been empty for the past couple of years. “It’s difficult to go to the jungle because of the tiger,” she said. “There is no fodder at home, so we cannot keep the cattle in the cattle shed. In the jungle, tigers attack the cattle.” Rana Magar, who has taken a loan of Rs100,000 to look after her family of eight, has now been preparing to send two of her sons abroad.

Pushpa Tamang

The lack of cattle means a lack of manure for the farms. According to Rana Magar, 10 quintals of mustard can be grown in one bigha of the farm if there is ample dung manure. However, she pointed to empty cattle sheds, “There are no cattle in the shed now. So how would we grow food?”

After the Banke National Park was declared in 2010 AD, the grassland within the national park in the Gabhar area on the northern side of the highway was closed for grazing and collecting fodder. The community and national forests of the southern area continued to provide opportunities for grazing and fodder. However, for the last three years, the striped tiger has become a regular presence in the community forests of the south. The villagers, thus, have not been able to venture into the forests ever since.

Having failed to go into the jungle, Pushpa Tamang, a resident of Gabhar, who used to rear 45 goats and a few cows and buffaloes, has left her cattle shed empty for the past two years. She was attacked by a tiger on July 5, 2020, when she was in the Durga Community forest to collect fodder. Only when her fellow villagers shouted did the tiger run away, leaving Pushpa injured.

Her livelihood depended on the sale of goats when she reared them. However, having no goats to sell now, she is reeling under financial stress. Pushpa’s husband is a daily wage labourer whose earnings hardly pay for her medicine and household expenses. “I spend Rs6,000 a month on medicine. I faint if I do not take medicine,” she told the Centre for Investigative Journalism.

In Gabhar, a tiny village of 80 households, cattle rearing was the primary income source before the tiger problem began. “Many villagers have stopped rearing cattle after the number of tigers increased,” said Iman Singh Tamang, 81, a village elder. According to the National Nature Conservation Trust, five people were killed in tiger attacks last year. Four of them were killed outside the National Park and one inside it.

After the tiger attacks increased in community forests near villages, villagers from other villages stopped rearing cattle. Shiva Bahadur Thapa, a resident of Rapti Sonari-4, used to raise 10 goats. Three of them were killed in tiger attacks, and Thapa sold the rest. “The goats are attacked by the tiger the moment they step out of the enclosure,” said Thapa.

Geeta Adhikari, a resident of Rapti Sonari-6, had 15 goats. But now, she has sold all but two. Govinda Bista, a resident of Rapti Sonari-4, had nine goats. But he kept only two when his mother was attacked by a tiger when she was out in the jungle to collect fodder.

According to Hari Bahadur Tharu, social mobiliser of Rapti Sonari-6, the number of villagers rearing cattle has declined due to the fear of the tiger. “Even those who rear the cattle are rearing too few of them. As a result, the villagers have lost their incomes, many of them finding it difficult to sustain their livelihoods,” Hari Bahadur said.

Janak Bahadur Tharu, a former chairperson of Rapti Sonari-6, said the villagers were living in fear due to the increase in tiger count. “We must go to the jungle to collect fodder, leaves and firewood. But the people are terrified,” Janak Bahadur said.

“We developed community forests, but now we have become victims”

In the Tharu settlement at Hakrahawa in Rapti Sonari-6, preparations for the Maghi celebration had already begun. Family members working away from home had already returned. Chandani Tharu, 34, was gathering materials for the festival.

On January 11 this year, Chandani’s husband went to a nearby village for work. Chandani went with her neighbour to the Siddheshwar Community Forest, three kilometres from home, to collect sal leaves and make leaf plates. But Chandani, who had left her two children with her mother-in-law, could not return home as a tiger killed her.

Chandra Magar’s empty shed in Banke’s Gavar.

Just five days before Chandani was killed, Leela Bista, a resident of Rapti Sonari-4, was killed when she had gone to the Jalan Community Forest to collect fodder. Dhan Bahadur Chalaune, a resident of Rapti Sonari-6, was killed in a tiger attack on 7 Falgun, 2078 when he went to repair a canal near his home. Examples of people being attacked and/or killed by tigers in or nearby community forests and national parks are aplenty. Such areas, where tiger attacks have been frequent lately, were open grasslands just a decade ago. Such forests, developed by community members after years of effort, have become dangerous, says Jogendra Mahato, chairperson of Janakauli Buffer Community Forest.

The Shiva Community Forest in Bardiya district’s Madhuvan Municipality-1 was also an open grassland until 25 years ago. According to Mangal Tharu, chairperson of the community forest, after the locals turned the grassland into a forest, it has become a habitat of tigers and rhinos.

Growing more tigers is good. But what about human safety?

The establishment of the Central Investigation Bureau (CIB) and the World Wildlife Control Unit, the improvement of the tiger corridor and the cooperation with the local community, are the steps taken to increase the number of tigers. CIB has in the past five years arrested 309 people on charges of wildlife trafficking.

Locals collecting firewood at Shiv Community Forest in Madhuvan, Radiya.

The government succeeded in increasing the number of tigers, but it did not devise any alternative plan to solve the crisis the increase in the number of tigers had brought to humans. Due to this negligence, people have been killed or injured, or have lost their livelihoods.

According to Advocate Dil Raj Khanal, an expert in laws related to natural resources management, the government that has worked towards increasing the number of tigers has failed to provide communities with alternatives to fodder and firewood, thereby leaving them dependent on the jungle.

True, the government does not cooperate with the local communities except when bringing the dead bodies of victims outside of the jungle after tiger attacks. If the victim was killed outside of the national park, their family receives compensation of Rs1 million. Acharya, the former director-general of the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Department, concedes that although the government has focused on the distribution of compensation, it has not been able to reduce the number of tiger attacks on humans. “When the tigers grow in numbers, they do not just stay inside the jungle. It was a mistake not to think about what to do when the tigers came out, leading to a conflict with humans.”

Govinda Bista, who lost his mother to a tiger attack in Rapti Sonari-4 on January 6 this year, told CIJ-Nepal, “The government should give us a job. We will use gas rather than firewood for cooking and not rear cattle. We will not even go to the jungle.”

Bishnu Budhathoki of Madhuvan 3 of Bardia showing scars of the tiger’s paws. Photo: Janu Pandey

The government, meanwhile, thinks the community is responsible for the deaths of the people in tiger attacks. According to Ram Chandra Kandel, who has just been transferred to the REDD Implementation Centre from the director-general of the Wildlife Conservation Department, the people do not have the luxury to go to the jungle whenever they like.

“You should go to the jungle in a group, and should not go anytime you like,” Kandel said, adding, “It is only natural for the tiger to eat you if you visit the jungle alone.”

Meanwhile, advocate Khanal says the local community should be allowed to use natural resources for free, and they should be provided with alternatives for livelihood. Khanal believes that the locals who have faced the maximum damage are the ones who face discrimination when it comes to the distribution of benefits.

“It is true that human activities have become a conservation challenge. However, the narrative created by the government that anyone who goes to the jungle naturally risks tiger attacks is problematic,” said advocate Dil Raj Khanal. “To be able to visit the jungle is a basic human right.”

Creating job opportunities for local communities and lessening their dependence on the jungle is the government’s responsibility and the institution active in conservation. However, Nepal’s rural communities’ direct reliance on the jungle continues.

Mangal Tharu, a resident of Madhuvan-1 in Bardiya says nobody has helped in lessening the community’s foray into the jungle. “Except for operating the Tharu homestay, nobody has helped the villagers lessen their dependence on the jungle,” Tharu said. Sudeep Yogi, another resident of Madhuvan, says even those who helped the villagers provided them with more goats, which means that the villagers have to visit the jungle even more.

To ensure communities’ livelihood and wildlife conservation, the World Wildlife Fund has initiated the Terai Arc Landscape (TAL) project that covers the area from Bagmati in Rautahat to western Kanchanpur. However, the locals complain about this programme.

Seeta Acharya, a resident of Madhuvan-3, says the conservationists first asked them to grow the jungle for fodder and firewood; but now, with the increase in tigers, they have asked the locals not to visit the jungle. “First they asked us to grow the jungle in the name of fodder and firewood. We believed them and turned the jungle into a community forest. Now the tigers have started to visit our homes, and these conservationists asked us to save the tigers,” said Acharya.

Human cost

Before 1951, tigers were found in the lowlands from east to west and in the Chure area. For the aristocrats, hunting a tiger was a hobby. Members of Rana families and royal families spent their winters hunting in the jungles of Terai.

Bishwonath Upreti, the first director-general of the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Department, has written in his book Early Days of Conservation In Nepal that Junga Bahadur Rana, during his 1850 hunting trip, killed 31 tigers, 21 elephants, three cheetahs, four bears, 20 bucks, and one rhino. There are ample details of King Mahendra inviting foreign guests for hunting trips. Until 1968 AD, it was a matter of luxury and pride among aristocrats to hunt wildlife.

Bishnu Budhathoki

People from the hills began to descend to the Terai after malaria eradication. The number of tigers and other wildlife began to decline due to hunting and human encroachment into the jungles.

It was only then that the government began the conservation campaign from Chitwan. The National Wildlife Conservation Act was promulgated in 1972 AD, and the Chitwan National Park was established in 1973 AD.

The conservation practice in Nepal has gained global recognition. However, the debate today is: At what cost are we raising the numbers of tigers?

Today, there are 12 national parks, six conservation areas, one hunting reserve and one wildlife reserve in Nepal. These areas together cover 23 percent of Nepal’s total land. According to the ministry, Chitwan National Park has 128 tigers, Bardiya National Park has 125, Parsa has 41, Shuklaphata has 36, and Banke has 25 tigers.

The National Park and Wildlife Conservation Department in 2020 published a report titled Assessment of Ecological Carrying Capacity of Royal Bengal Tiger In Chitwan Parsa Complex, which says the Chitwan National Park can accommodate 136 tigers and the Parsa National Park can accommodate 39 tigers. The report came with these numbers based on the availability of prey species necessary for the tigers.

Meanwhile, the locals who supported conservation activities have now started questioning the idea of conservation.

When Ashmita Tharu, 41, a resident of Madhuvan-2 was killed in a tiger attack on June 6 this year, the locals obstructed the Gulariya-Rajapur road section while asking for security. When the police opened fire in an attempt to remove the obstruction, Kaushila Pal, a local, was killed. As the animal attacks show no sign of declining, Hari Gurung, Khata Community Forest Coordination Committee chairperson, said, “What did we get by increasing the number of tigers?”

People have depended on the jungles for fodder, fuel, vegetables, herbs and rituals. Even today, people living near the jungles depend on jungles for their livelihood. According to Sati Sharan Tharu, a resident of Rapti Sonari-6, there will be no fire in his hearth if he does not visit the jungle.

The problem seems compounded by the fact that the tiger conservation plan has been implemented without ensuring livelihood and alternative provisions for the locals. “What is the point of having tigers and forests if people do not survive?” asked Sonari. “What could be the opinion of the people here who have had to keep their children hungry in the name of saving tigers?”

According to Krishna Prasad Acharya, former director-general of the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Department, the idea of developing community forests outside of the national parks was to lessen the dependence of the locals on the national parks for grass and firewood. “The problem occurred when the buffer zone outside the national park was developed just like the national park,” Acharya said.