With haphazard extraction of riverbed material in Bheri river, a Surkhet village is at risk of being swept away. With local unit’s complacency, the villagers fear displacement.

Laxmi Bhandari | CIJ, Nepal

Neglected by the local unit, the residents of Raji village in Panchapuri Municipality-9, Surkhet are now worried about the prospect of having to relocate from their settlement.

The village is vulnerable to flood since the 2014 Bheri flood wreaked havoc in the settlement. Moreover, the haphazard extraction of riverbed material at major cross-section risks the river changing its course and entering the village, say villagers.

These days, Kamal Sapkota, a local, spends most of his time chasing away tractors and tippers that come near his home to extract sand and pebble. “The vehicles come in droves. Blink and you miss it,” he says. “I need to patrol the area even in the night to save the village.” But despite Sapkota’s and other villagers’ efforts, the illegal extraction hasn’t stopped.

Locals obstructing vehicles arriving to extract riverbed material.

On 14 August 2014, the Bheri flood had swept away Gangaram’s wife and their home. Gangaram is a local of Panchpuri Municipality-5. After that, he and his two children have been taking shelter at his brother’s home in Rajigaun, in ward 9. “We don’t know when the flood would enter the village again,” says Gangaram. “Once the monsoon starts, we’ll have to stay awake all night.”

That year, the flood claimed the lives of 31 people in Surkhet, mostly around Raji gaun. A total of 214 households was displaced. Most of the displaced are sheltered in Kalika Community Forest.

Rima Karki, a 40-year-old from Raji village, says, “We can’t hold a sit-in protest at the river all day, and the tractors and tippers keep coming. If this continues, we’ll get displaced soon.”

In this flood-prone area, the Panchapuri Municipality had granted a contract to extract riverbed material to Durga Construction on November 2020. But the contract was called off after the locals’ protest. “The contract didn’t follow procedures of the environment impact assessment (EIA),” says Mohan Malla, an engineer formerly with the municipality.

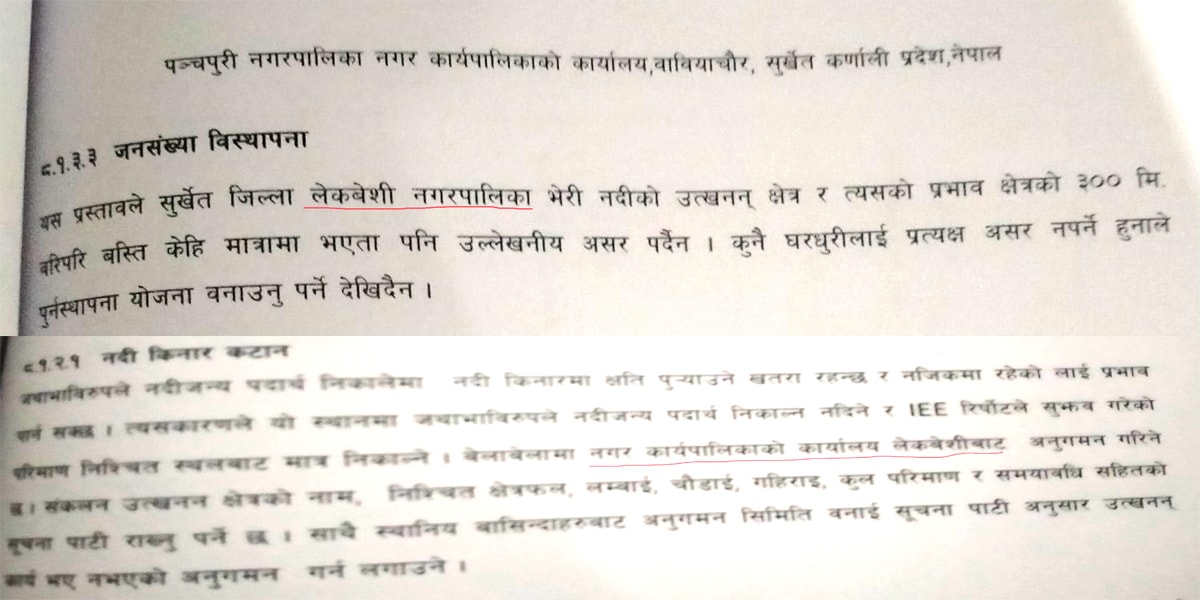

The EIA report, however, was not carried out visiting the location. It was rather copy-pasted since it misstates the name of the municipality, Lekbesi in place of Panchapur. This time around, the municipality has permitted extraction at about 500 meters away from the previous one. But extraction at the edge of the village continues. Often the villagers protest and turn the vehicles back but it is not possible to do that at all hours of the day.

Emphasis on sand and pebbles

Scared by the flood of 2014, the villagers have been demanding the municipality to stop the extraction and construct an embankment. But the municipality offered contract to extract material from the very high-risk location instead. “It appears they won’t let us live quietly here,” says Junikala Raji, another local. “Last year, we protested for a month, but that amounted to little effect.”

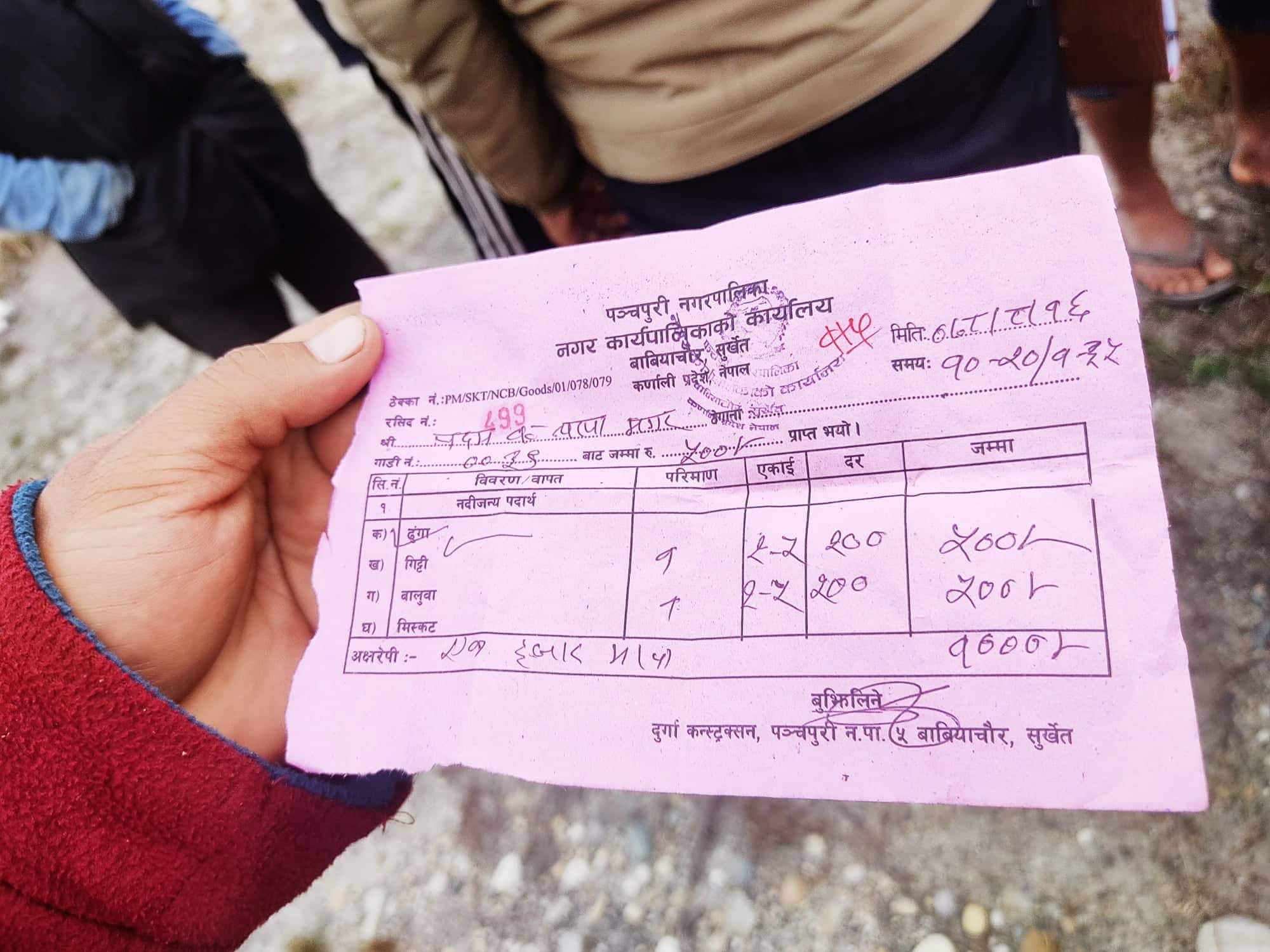

Last year, the municipality had changed the status of river to a rivulet and granted contract to Durga Construction to extract 53000 cubic metres of riverbed material. The contract was canceled after the locals protested forming a struggle committee. But even though the contract is cancelled on paper, the extraction continues.

The customary fee taken by Durga Construction out of the material.

“Since the extraction takes place at the very place where the river is most likely to change its course, there’s risk that the event of 2014 will repeat,” says Kamal Sapkota, the coordinator of the committee. “We have demanded for a construction of the embankment but the municipality hasn’t listened to it.”

Sapkota adds that the police has colluded with the contractor and has threatened and even arrested the committee members. In November 2021, when three men, Kamal Poudel, Umesh Chand, and Chhabilal Sapkota seized the vehicles’ keys, they were summoned to the police office, says Sapkota.

Even though the village lies at a lower altitude than where the river flows, it was more or less safe till now because the place where the river could change its course is at a higher altitude. With growing extraction, that safeguard could be nonexistent. “If an immediate action is not taken, by putting a ban on extraction and constructing embankment, the whole village risks deluge coming monsoon,” Sapkota says.

Political colors

The Raji community, which makes a living out of fishing, has been living at the areas since before 1963. Madan Raji, 52, says the 2014 flood was the first he knew in the village. “The haphazard extraction is the root cause,” he says, adding that the extraction has also robbed them of their source of income, fishing.

The village constitutes of over 100 households from Raji, dalit, and other indigenous communities. Of them only nine are Rajis. And the village is the major habitat of Rajis in the district. Shanti Kharal, the chair of ward 9, where Rajis are based, and Upendra Bahadur Thapa, the Mayor, are from different political parties. Because he received few votes from the ward in local elections, Thapa is resentful towards the ward, says Kharal. “It is evident that the mayor is openly discriminatory because there is an embankment on only one side of the river,” he says.

Locals patrolling the vicinity to obstruct extraction.

Sapkota, the committee member, also shares in Kharal’s opinion. “The mayor doesn’t seem concerned in saving our village,” says Sapkota. Laxmi Barali, a ward members, also says that the mayor hasn’t paid heed to their demands to construct an embankment. “Development only reached the village across the Bheri. We feel discriminated,” she says.

Local activists say there is no other recourse than minimizing the risk of flood through embankment. “The whole village risks being desertified,” says Mohan Baduwal. “Either an embankment needs to be constructed or the whole village be relocated.” Baduwal adds that the problem arose because there was no study on the environmental effects of extraction.

‘Better to have fished for gold’

Romkanta Pandey, chief administrative officer of the municipality, expresses ignorance on the matter because he was recently posted to the district. But the municipality cannot construct the embankment, he said. “I was not here when the contract for extraction was granted, and we had posted a tender notice this fiscal year, which we have already cancelled,” he said.

Mayor Thapa says since the embankment requires a large budget, he is demanding that with the federal government. “An embankment there needs about 60million rupees, which we have asked with the federal government but haven’t received response,” he says.

The copy-pasted EIA report.

Thapa claims that there was no extraction in high-risk places and there was no discrimination in budget disbursement. “I haven’t discriminated against anyone,” he says. When asked why the embankment was constructed on only one side of the river, he says, “People will say anything they like. Development is a gradual process.”

In 2015, a Chinese company had extracted material in the river to locate a gold mine. The move was carried out in then Finance Minister Krishna Bahadur Mahara’s direction and was not approved by the local administration, say locals.

After protests, the extraction was discontinued. “The Chinese company had brought big machines here,” says Khagiram Sapkota, another local. “The machines would run throughout the night. That extraction had created a mountain of riverbed material which is saving the village till now.”

Another local Bishnu BK says, “I don’t know whether that extraction located gold but it has saved our village. Better to have fished for gold than sand.”