What impact do strict laws and inadequate investigations into wildlife crimes have on the Chepang community in Chitwan? The story of Rajkumar Praja’s family in Korak serves as an example of those seeking an answer.

Tufan Neupane |CIJ, Nepal

At Tribhuvan International Airport, a Central Investigation Bureau (CIB) team anxiously awaited the arrival of a high-priority “international criminal.” On February 8, 2015, at 1 pm, when flight MH 0170 G6 from Kuala Lumpur touched down, the police were on high alert. Police seized and handcuffed a middle-aged man as soon as he stepped outside the aircraft wearing a long-sleeved T-shirt and shorts.

In the right pocket of his shorts, the man’s transfer to the Central Investigation Bureau revealed a passport and boarding card with the number 05502408 issued in the name of Bhaktaraj Giri. Additionally, they found on him a letter with details regarding employment abroad and a one-way travel document issued by the Nepali Embassy in Kuala Lumpur.

Home of Praja families in Kalikhola.

The person who was apprehended described himself as Krishna Bahadur Giri’s son from Gorkha Municipality-4 and was in possession of a citizenship document (No. 441001/2749) issued by the Gorkha District Administration Office on May 26, 2010, bearing the name Bhaktaraj Giri. Based on this, he applied for a passport with the number 4720464 and left on October 12 for a business trip to Malaysia.

He lost his passport in Malaysia, and on March 17, 2011, the Nepali Embassy issued him a replacement (passport number 05502408). He was taken into custody by Malaysian authorities on January 30, 2015, for using a false passport. He was sent to Nepal after nine days.

The CIB team at the airport was not waiting for Bhaktaraj Giri, a man from Gorkha who went to Malaysia for employment and was accused of using a fake passport. They were waiting for Rajkumar Praja (31 years old at that time), aka ‘Kalikhole Kancha’ of Korak, Chitwan, who had been wanted by the CIB for 10 years for killing at least 21 rhinos and selling their horns, and had an Interpol Red Corner Notice in his name.

To evade arrest, Praja had used fake documents under the name of Bhaktaraj Giri to fly to Malaysia. On the request of CIB, the Malaysian police arrested him and returned him to Nepal.

A smuggler boss or just a mule?

Khurkhure Chowk is situated approximately 20 km to the east of Narayanghat Bazaar. From Narayanghat Bazaar, it takes about 30 minutes to reach Samitar by traveling north. Once the tarred road ends in Samitar, Kalikhola can be found about 3 km to the northwest. Korak, which was previously under the jurisdiction of the village development committee of the same name, now falls under Rapti Municipality Ward No. 10. There are four houses across the river that share the same courtyard.

The house on the far right belongs to Rajkumar Praja, the other three houses belong to his brothers. When we went to his house in December, his wife Motimaya (36 years old) had just returned from threshing corn in the field. This land is unregistered; they plant two crops of corn, and paddy in the dry season, but it’s not enough to sustain them throughout the year, Motimaya said.

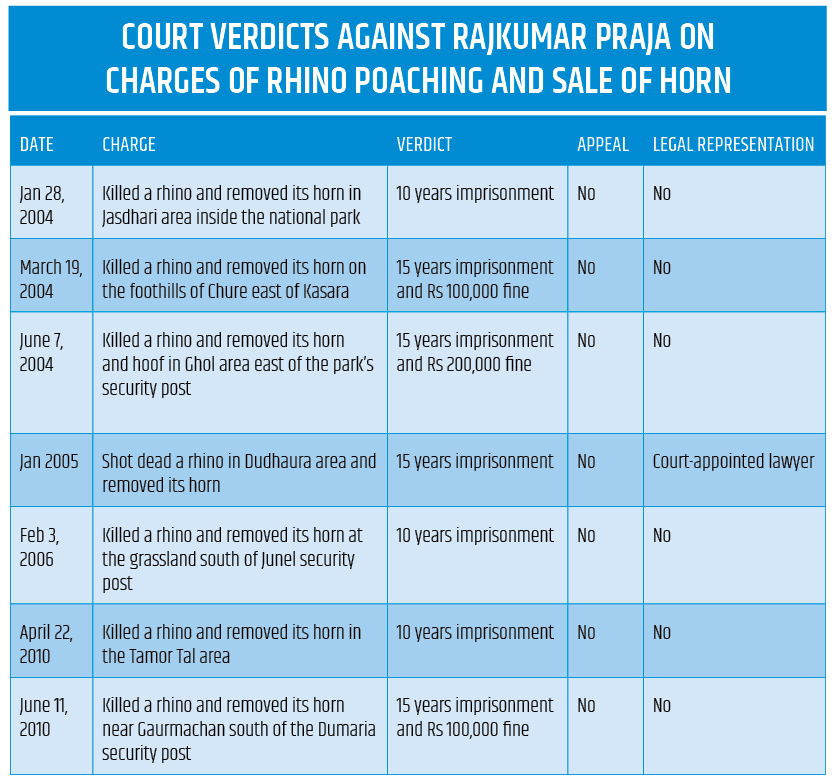

Rajkumar has been accused of killing at least 21 rhinos in Chitwan between 2004 and 2011 and smuggling them out. After being brought back to Nepal, he was first apprehended by the national park. Before the 2015 constitution, all wildlife crime cases were first heard by park authorities. However, after the constitution stipulated that initial proceedings should only be conducted by district courts in offenses punishable by imprisonment for more than one year, the cases against Praja were transferred from the park to the district court. In 2016, Judge Teknarayan Kunwar passed a verdict that 10 individuals, including Praja, should be incarcerated for 15 years and one person should be imprisoned for seven years.

The verdict states that Praja was directly involved in the criminal activities from start to finish, such as planning to kill rhinoceroses, acquiring firearms and ammunition, illegally entering the park to kill the rhinoceroses, cutting the horn, preparing it for sale, selling it and distributing the proceeds. For this charge, he received the maximum possible punishment as stipulated by the National Parks and Wildlife Protection Act. The Act provides for imprisonment of five to 15 years or a fine of Rs 500,000 to Rs 1 million or both.

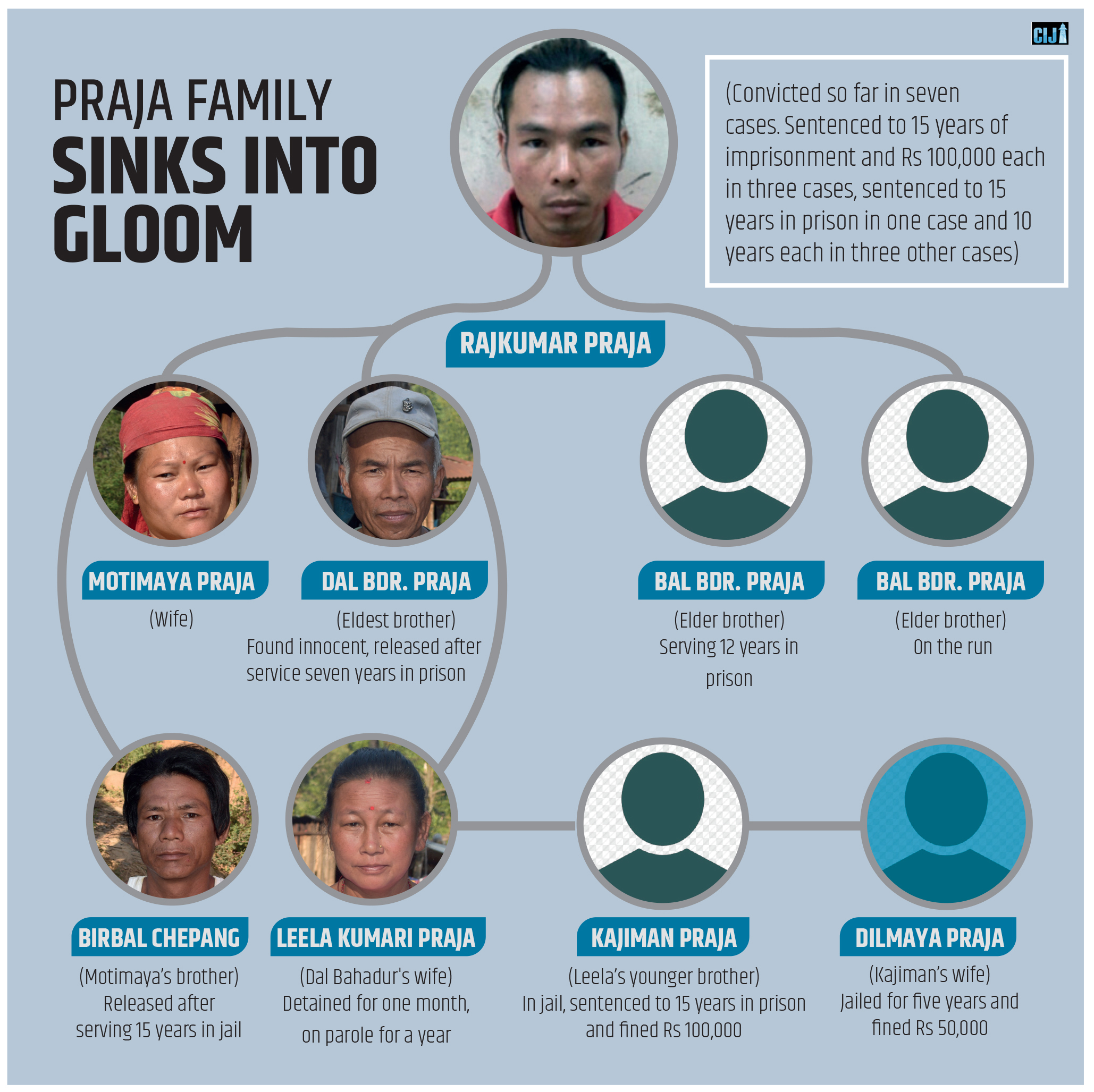

The verdict describes Praja as a ‘notorious trafficker’ involved in the illegal business of poaching and selling rhino horns. Although the verdict accuses him of involvement in the theft and poaching of 21 horns, it hasn’t been proven that he killed such a large number of rhinos. So far, he has been convicted in seven cases. The court sentenced him to 15 years imprisonment and a fine of 100,000 each in three cases, 15 years imprisonment in one case, and 10 years imprisonment in cases.

In Rapti-10 Kalikhola of Chitwan, the Praja family has been struggling with extreme poverty for years after the imprisonment of head of the household, Rajkumar Praja. This has left his wife Motimaya to shoulder the responsibility of caring for their son, daughter-in-law, and three-year-old granddaughter. The couple’s teenage sons and daughters-in-law are also without income. The family’s financial struggles have also affected the education of their 19-year-old son, who dropped out of school after tenth grade, and their daughter-in-law, whose education was halted due to her early marriage.

“Life is difficult. My husband has been jailed and now I am left to take care of a family of five by working as a daily wage earner,” said Motimaya. “Some organisations support people from the village released from prison in their ventures. However, there is no support for the families of those who are currently in jail.”

Motimaya said that Rajkumar has been in Birgunj jail for three years. Due to financial constraints, she has been unable to visit her husband who is located 130 km away from home. Communication with her husband has been limited as the family can’t afford to pay for phone calls. “We couldn’t hire a lawyer without money as the lawyer charges Rs 15,000 for each appearance before the court,” she said. “The verdict was passed based on allegations made by the national park. We can’t afford to travel and meet him.”

Rajkumar’s wife Motimaya (36) with her granddaughter.

When Praja was sentenced to jail, it appears that he was unable to hire a lawyer for his defense. In only one of the seven cases in which he was found guilty, a court-appointed lawyer, Tirtharaj Pokharel, pleaded on his behalf. However, the lawyer did not plead Praja’s innocence. His only claim was that Praja should receive the minimum possible punishment as he had accepted all charges against him and assisted the court. However, the court didn’t agree and sentenced Praja to a maximum of 15 years in prison.

It is unclear why Praja, accused of making a substantial income from smuggling a large number of rhino horns, was unable to hire a lawyer for his own legal defense. It is possible that he didn’t have the financial means to pay for legal representation, or that he was unable to find a lawyer willing to take on his case. Alternatively, it could be that Praja was a small-time operator hired by larger criminal organisations for a minimal amount, and therefore didn’t have the resources or the connections to secure legal representation.

It is not clear from the information provided whether the individuals or organisation behind the illegal trade of rhinoceros horns in the international market, who likely profited greatly from this illegal activity, faced any consequences or are receiving immunity. The investigation and the case of Rajkumar Prajkumar only provide a glimpse into the issue, and it is possible that the larger criminal network behind this illegal trade may not have been fully exposed or brought to justice.

“We have no knowledge of what happened in the court. I don’t know for how many years he will have to stay in jail, when he will be released, or if he will be caught in another case after he comes out. I don’t even have that information,” said Motimaya.

Destruction everywhere

Rajkumar Praja’s family relocated from Shaktikhor in Chitwan to Korak in the late 80s. His brother-in-law, Ramkumar, is also currently on the run after being charged with rhinoceros poaching. Rajkumar’s elder brother, Bal Bahadur, is currently serving a 12-year sentence for the same offense.

On February 23, 2011, a joint patrol team of the anti-poaching unit of the park arrested Suman Bamjan, a resident of erstwhile Siddhi Village Development Committee-2, based on an informant’s tip that a rhinoceros had been killed and its horn sold. Bamjan, during the investigation, provided the names of several individuals involved in the illegal act, including Rajkumar Praja, Rajkumar’s brother Bal Bahadur Praja, another person named Rajkumar Praja aka ‘Kancha’, Ramesh Tamang, Sher Bahadur Chepang, Dil Bahadur Praja and another person named Bal Bahadur Praja aka ‘Bame’. Authorities arrested Rajkumar’s brother Bal Bahadur Praja based on the information provided by Suman Bamjan.

Dal Bahadur Praja, who was acquitted after spending almost 7 years in prison.

During the investigation and court proceedings, Rajkumar Praja denied the accusations made against him, stating, “It is not true that I went to kill a rhinoceros in the park in April 2010 and gave Rs 50,000 to Suman after selling the horn. I do not know Suman and I have not killed or sold any rhinoceros horns. I do not understand why I have been falsely accused.”

The testimony of Suman Bamjan, the informant, is questionable as he named Bal Bahadur Praja aka ‘Bame’ as one of the eight people active in killing and poaching rhinos with him on April 19, 2010. However, it was established that Bal Bahadur had already been arrested on August 4, 2003 and was serving a 15-year prison sentence in Kaski Jail for another case of killing rhinos.

It appears that park officials did not have any other evidence against Bal Bahadur (Rajkumar Praja’s elder brother) besides the testimony of Suman Bamjan when the verdict was issued. Despite this, Chitwan National Park decided on June 30, 2015, to sentence Bal Bahadur Praja to 12 years in prison for killing rhinos and selling their horns

In July 2017, the Hetauda High Court upheld the decision of the Chitwan National Park. Bal Bahadur, who was arrested in January 2015, has been serving a 12-year prison sentence in Bharatpur jail since then.

After Bal Bahadur was jailed, his wife remarried. Their son Ashish, who was in sixth grade at the time, was unable to continue his education. Eventually, Ashish married his schoolmate Kalpana. They now have a young daughter. “We are poor and can’t afford to continue our education,” said Bal Bahadur’s daughter-in-law Kalpana. “It’s difficult to make ends meet. My father-in-law has been in jail since before my wedding, I don’t know how he is. My mother-in-law had to remarry because it was hard to manage the household alone.”

Rajkumar’s elder brother Bal Bahadur, was released from prison after serving seven years, as he was found to be innocent of the charges of being involved in the theft and poaching of rhinoceros.

Bal Bahadur had gone to Saudi Arabia for foreign employment and returned home. He was scheduled to fly to Saudi again on July 18, 2010. However, on June 28, before leaving, he visited the house of his father-in-law, Bijram Praja, who lived in Korak-9 Chipleti, to build a toilet. His brother-in-law Kajiman was building a new house by connecting it to Bijram’s house. He had invited his sister Leela Kumari and brother-in-law Dal Bahadur for a feast. While they were eating, security personnel from the park surrounded the house and arrested Bal Bahadur, his wife Leela, Jit Bahadur Pun, Shakti Praja, Buddhi Bahadur Praja, Durga Bahadur Tamang, Mahendra Gurung, Kajiman’s wife Dilmaya, and others.

Two weeks prior to the arrest, on June 11, 2010, a 20-year-old male rhinoceros was found dead in Chure Ghanch Salghari, south of Dumaria post near Gauramchan, about 200 meters west of Bans river.

Based on a tip-off, security personnel concluded that the rhinoceros was killed by Jit Bahadur Pun and Kajiman’s group. Therefore, Kajiman’s house was raided.

Despite Kajiman being able to evade arrest, his wife Dilmaya, sister Leela, brother-in-law Bal Bahadur, as well as the construction workers Tamang and Gurung were apprehended by the security personnel. They filed a case against Rajkumar and Kajiman along with the arrested individuals. Leela was let go on the condition that she would attend any future hearings or summons from park officials after spending a month in detention.

Bal Bahadur Praja had been in prison for nearly three years when the park passed the verdict that he was innocent on June 12, 2013. Despite the government’s appeal against the decision, the Hetauda High Court also cleared him of charges in January 2015. The Supreme Court later declared him innocent in March 2017. However, as he was a defendant in another case, he was immediately arrested and sentenced to another 10 years in prison. But he was acquitted again in February 2018 after appealing to the High Court in Hetauda. In total, he spent seven years in prison from the time of his arrest in 2011, despite his innocence.

Kajiman, the brother-in-law of Bal Bahadur, was arrested later. On June 12, 2013, the National park sentenced him to 15 years imprisonment and a fine of 100,000 rupees. His wife Dilmaya was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment and a fine of 75,000 rupees. Kajiman is still serving his prison sentence without even appealing it.

“Our family was devastated when the man who was trying to go abroad was caught and imprisoned for seven years and I was also imprisoned for a month,” said Leelakumari. “My brother Kajiman has been in prison for 15 years. My sister-in-law Dilmaya was also released after spending five years in prison. The situation of our family has become dire.”

On September 21, 2013, Omprakash, the younger son of Dal Bahadur, passed away as a result of not receiving medical care while his father was serving a prison sentence. Leela, Omprakash’s mother, stated that she was unable to provide the necessary treatment for her son due to financial constraints. She said, “I couldn’t do anything, the son died without treatment. Hiring a lawyer was too expensive for me, I could barely afford to pay for my son’s treatment and my daily expenses with the money I made selling goats.”

Before being incarcerated, Dal Bahadur, who was working abroad, was able to support his children’s education. However, upon his imprisonment, the family’s source of income was cut off and their children’s education was disrupted. His daughter got married, his elder son became idle, and his younger son passed away.

“I couldn’t sleep in jail thinking about my family’s struggles,” he says, “I was declared innocent after being imprisoned for seven years, but where do I go for justice? Who will be held accountable for the financial expenses of my imprisonment, the hardships my family faced, the embarrassment my children endured at school, and the lost income?

‘Wouldn’t wish it even for man who ran away with my wife’

Nepal’s laws on wildlife crime are among the strictest in South Asia. According to the National Parks and Wildlife Protection Act, penalties for such crimes include a prison sentence of five to 15 years, a fine of Rs 500,000 to one million, or both. The case of Rajkumar and Motimaya’s family illustrates how local, indigenous communities are disproportionately affected by these strict laws. While multiple family members, including her husband and brothers-in-law, are currently serving time in prison for wildlife crimes, Motimaya and her siblings have also been deeply impacted.

Birbal, the brother of Motimaya, was freed after spending 15 years behind bars. At the time of his arrest on July 22, 2005, he was 25 years old and was a farmer supporting his family of four sons and a wife. Birbal confessed to providing assistance to a group of rhinoceros hunters in a park by cooking for them for Rs 2,000, but he denied any involvement in the killing of the animals or profiting from the sale of their horns. Despite his claims, he was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Virbal Praja, who was released after spending 15 years in prison on the charge of smuggling rhino horn.

Upon completion of his sentence, Birbal returned to find his family in shambles. His wife had moved on and remarried, his sons had abandoned their education, and his home was nowhere to be found.

“They said the Chepangs killed a rhinoceros. We were subjected to detention, arrest, and brutal beatings. Under duress, we were forced to confess to the crime,” said Birbal. “If someone’s name was extracted, they would be rearrested. This cycle of oppression continued for an extended period,” he added. “Many homes were destroyed, families were torn apart, and children’s education was sacrificed. Many suffered and died without receiving proper medical care.”

A number of young and teenage individuals from Korak were imprisoned at one point, losing their prime years in jail. Gradually, they are being released, among them Bir Bahadur Praja, Birbal Praja, Chandra Bahadur Praja, Mangal Bahadur Praja, Dal Bahadur Praja, Jit Bahadur Tamang, Jeet Bahadur Bal, Durga Rumba, Ramchandra Praja and others. Currently, Rajkumar Praja, Kajiman Praja, Ramesh Lama, Bal Bahadur Praja, Sher Bahadur Praja, Bir Bahadur Praja, Padam Bahadur Praja, Jeet Bahadur Tamang, Chandra Bahadur Praja, Dhanlal Praja, Dilman Praja, Sahakari Praja, Suk Bahadur Praja, Dev Bahadur Praja are still in jail.

“The families of those imprisoned are facing dire circumstances, with many children falling into addiction and some men losing their wives. Despite being accused of killing and selling rhinos, the financial situation of those like Rajkumar is dire,” Birbal, himself a former prisoner who served 15 years for a minor role in the alleged crimes, reflects on the devastation caused to his family and questions the effectiveness of such severe punishment for those who were only motivated by poverty. “What did the state gain by imprisoning a man for so many years for something as small as carrying goods for a few thousand rupees?” he asks.

Birbal, who saved 45 rupees daily from his allowance in prison and sent it home, had no family left upon his release after 15 years. He states, “This is my fate. When my time in jail was over, my life was also over. I wouldn’t wish this on even the person who ran away with my wife.”

Advocate Raju Chapagai states that many of those involved in wildlife crime in Nepal are poverty-stricken individuals who face severe consequences. He explains that wealthy and organised criminals exploit the poverty of local indigenous communities by using them as accomplices in hunting and transporting protected wildlife. According to him, this trend of the actual perpetrators escaping punishment has caused Nepal’s criminal justice system to require a review from the perspective of poverty.

Jails full of marginalised people

A study published in November 2019, authored by researcher Kumar Poudel and two others, presents an intriguing portrayal of individuals who have been imprisoned for crimes related to wildlife.

The study, based on interviews with 384 inmates, found that 61 percent of those incarcerated were charged with rhino poaching and trafficking in their horns. Around 56 percent of them were poor, 32 percent were illiterate, and 75 percent belonged to marginalised indigenous communities. These communities make up only one-third of Nepal’s population.

The findings of the study, which shows specific groups (poor, illiterate, indigenous) are disproportionately represented among those jailed for wildlife crimes, illustrates the unequal enforcement of Nepal’s severe wildlife crime laws. Additionally, 69.8 percent of the inmates interviewed stated that they were unaware of the potential penalties before committing the crime.

According to the study, wildlife criminals are present in 38 out of 74 prisons in Nepal. In most of these prisons, the percentage of wildlife criminals is low (ranging from 0.1 to 3.3 percent). However, the percentage of wildlife criminals is 21.1 percent in Chitwan prison, 9.6 percent in Bardia, and 6.4 percent in Rasuwa. The authors of the study state that many of these prisoners reported negative consequences such as their children missing education, losing their marriages, selling ancestral property, losing social prestige, family members changing religion, daughters not being able to get married, and in some cases, even suicide of family member following their imprisonment.

The responses of the prisoners highlight the impact of strict laws on wildlife crime on society. Advocate Chapagain suggests that there is a need for a national investigation by the Parliamentary Committee or the National Human Rights Commission. He further states that if necessary, the law itself may need to be altered.

An analysis of 30 judgments from the Chitwan District Court related to wildlife crime shows that individuals from the indigenous communities near the park have been prosecuted for involvement in poaching and trafficking of wildlife parts, and the majority of these cases have received the maximum possible punishment.

Residents who live near the park have a deep understanding of the wildlife habitats, migration routes, and patrolling routes of security personnel, so they are easily manipulated by wealthy and organized criminals to act as hunters and porters. Based on the prosecutions and court rulings, it appears that notorious wildlife traffickers are avoiding imprisonment.

Individuals such as Lodu Dime of Kathmandu, whose house was searched by police and 20 tiger whiskers were recovered, remain free. Ian Baker, an American citizen who allegedly posed as a journalist to collect rare wildlife parts in Nepal, is not facing legal action. Nitup Lama, who was involved in a large operation on the Nepal-China border 16 years ago, has also evaded prosecution. This list goes on. It appears that the main perpetrators of wildlife crime in Nepal are not held accountable while ordinary poachers and porters continue to face harsh punishment.

The Constitution of Nepal guarantees the right to legal representation for every person accused of a crime. However, many of these individuals, like Rajkumar Praja and his family, are unable to afford legal representation. Even though they can appeal to the Supreme Court in cases where the punishment is up to 15 years imprisonment, many accused individuals are unable to do so due to financial constraints. This lack of access to legal representation and fair trial rights is a violation of their fundamental rights.

The role played by various protected areas and national parks in the preservation of environment, nature and wildlife in Nepal is vital. Nepal has been showcasing this achievement as a benchmark in conservation on the global stage. However, the cost paid by individuals from indigenous communities such as Motimaya Praja who live near the park is not widely known.

Motimaya has many questions about her family’s current situation and her husband Rajkumar’s imprisonment. She questions, “Rajkumar was put in jail for earning millions by selling rhino horns, but where did that money go? Why is our situation like this? Why haven’t the people who made money by selling the horn been arrested?”

Published for the first time in Kantipur Daily on 21 January , 2023