The indifference of the Securities Board, responsible for safeguarding investors’ interests, is increasingly putting the public’s investments in the stock market at risk.

Sharmila Thakuri | CIJ Nepal

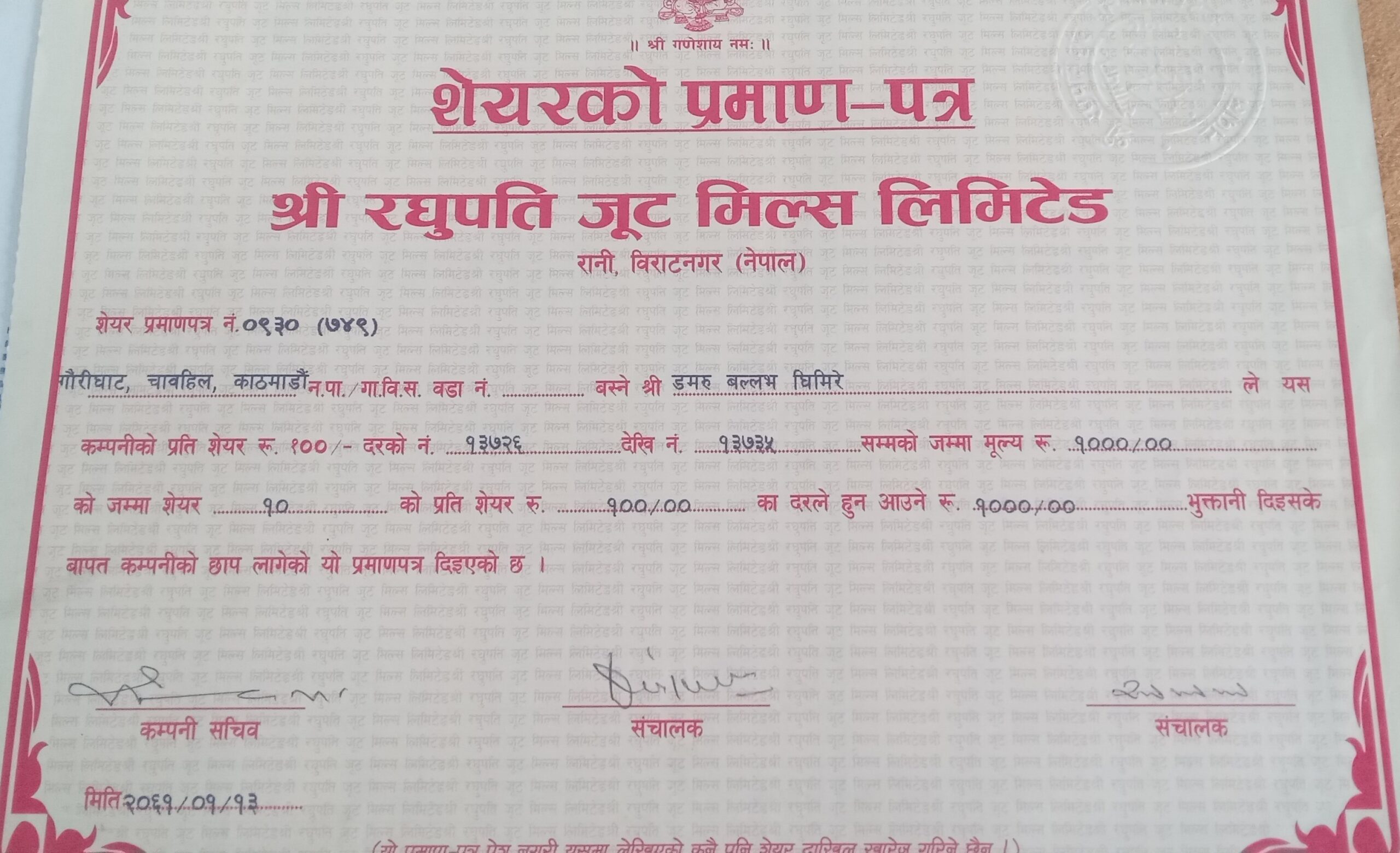

Damruballabh Ghimire sits in his room, spreading out share certificates from various companies. But most of these companies have never paid him dividends, and some have already shut down. In this digital age of the stock market, the 73-year-old Ghimire’s share certificates, piled up in his house in Gaurighat, are over two decades old. As he pulls out the certificate of Raghupati Jute Mill, he says, “It’s been 20 years since I bought shares in this company. Although the company has consistently been profitable, it has never paid dividends. The profits have been pocketed by the directors instead.”

Rajkumar Golchha, a director of the company, also asserts that the jute mill is profitable. According to him, the company made a net profit of Rs. 7 crore in the fiscal year 2079-80. He argues that since the company, which exports 90 percent of its products to India, reinvests its profits into the business, dividends have not been distributed. “The common shareholders of this company want dividends just like banking institutions tend to distribute, but in a manufacturing company, profits are reinvested in production,” he explains.

As the company has been delisted from the Nepal Stock Exchange, investors like Ghimire, citing the lack of tangible returns, cannot trade their shares in the secondary market either.

Chhotelal Rauniyar, former president of the Investors Forum Nepal, says that some companies deceive investors by using existing loopholes. He states, “It’s unjust if a profitable company neither pays dividends nor allows trading in the secondary market.” He argues that companies should not be allowed to delist themselves from the market after raising investments from the public. “Shares are liquid assets and should be sellable when desired. However, some companies have delisted after collecting investors’ money,” says Rauniyar. “This shouldn’t be allowed.”

According to the Nepal Stock Exchange, 65% of shares in Raghupati Jute Mills are held by Arihant Multi Fibers under the Golchha Organization, and 33.27% by the government. The remaining 1.37% of shares are held by 130 employees of the mill and the general public.

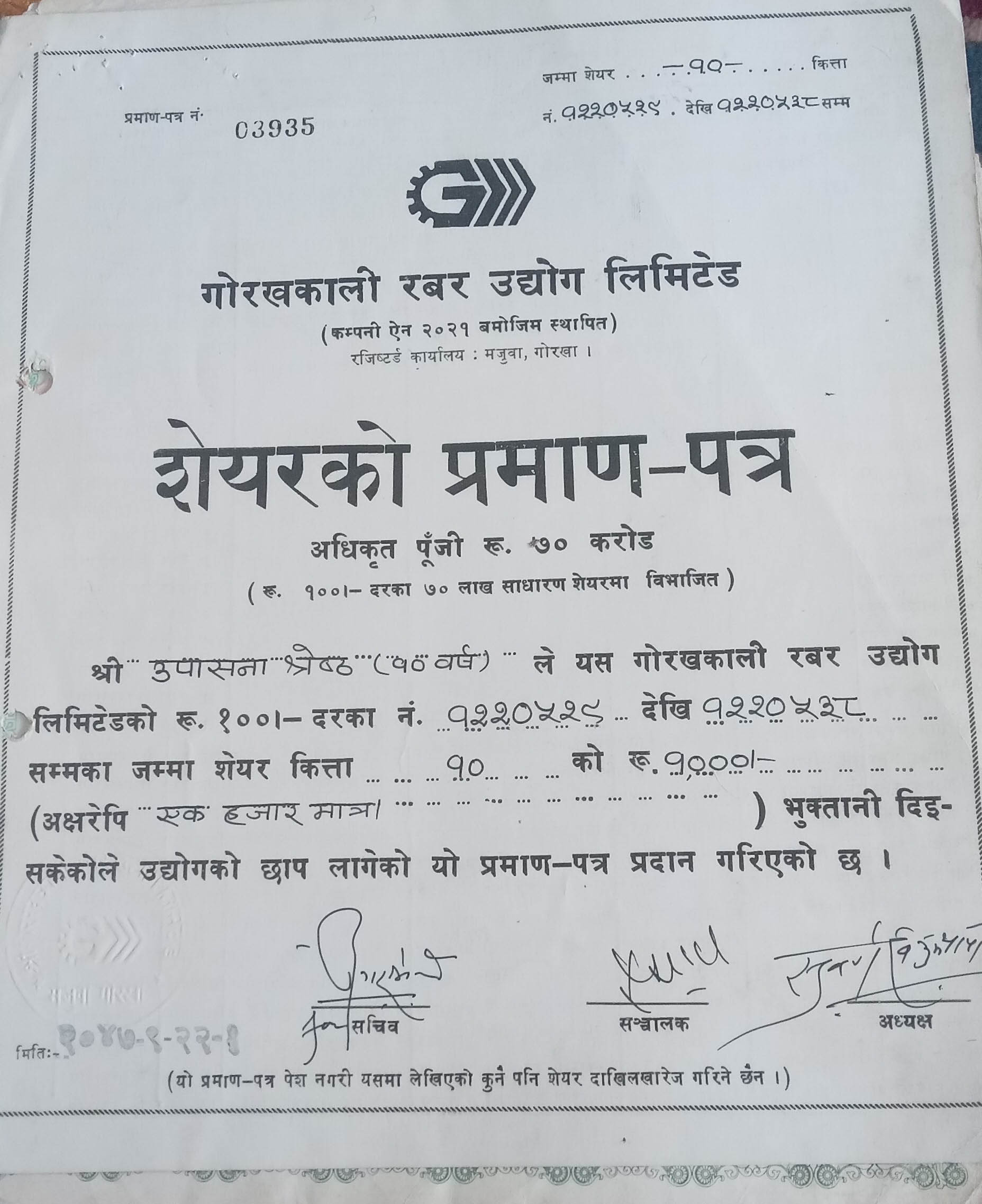

When Upasana Shrestha was 10 years old, she had invested in the Gorakhkali Rubber Industry. Now, at 44, however, all she has left is a deteriorating shareholder certificate. Despite being an investor for such a long time, she hasn’t received a single penny in dividends from the company. “My father invested in my name, and many in my family have invested in the company as well,” Shrestha says, “Money invested in other companies have multiplied several times over. If I had put that same amount in a fixed deposit instead, I perhaps would have made a good profit. Now, what’s the point of decorating this share certificate!”

The certificate showing procured shares of Raghupati Jute Mill

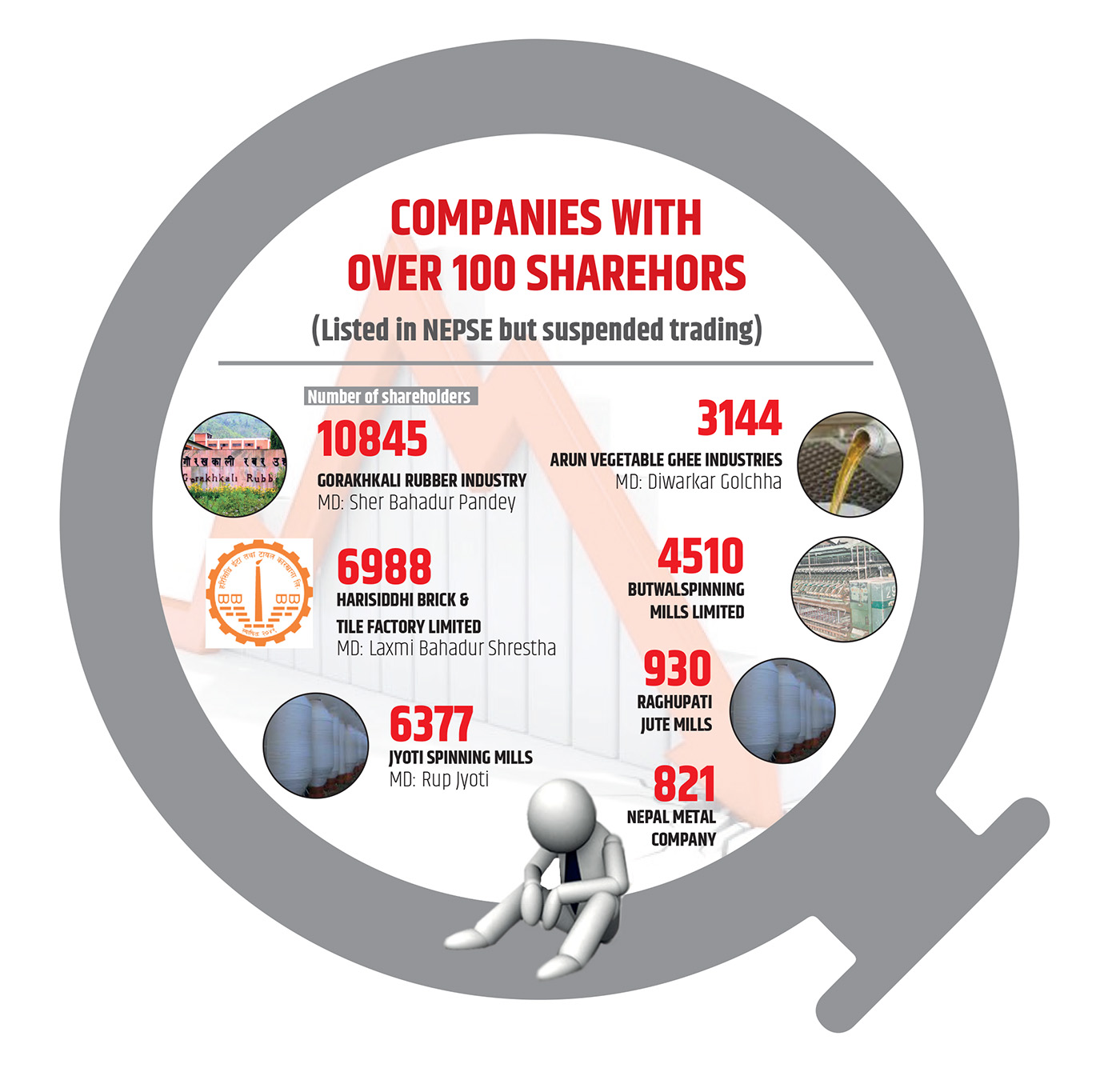

Gorakhkali Rubber Industry, under the ownership of the Nepal government, issued an Initial Public Offering (IPO) in 2047 BS. According to the Stock Exchange, the company, which had 10,485 shareholders, was 51% owned by Nepal Oil Corporation, Salt Trading Corporation Ltd., National Trading Ltd., and the Nepal Industrial Development Corporation (NIDC). The Asian Development Bank (ADB) held 13%, and general investors held 36%.

Due to political interference and arbitrary appointments, the company began to decline, leading ADB to sell its shares to Salt Trading. And after years of mismanagement, the company finally announced its closure in 2071 BS. However, the remaining shareholders have yet to receive any returns, let alone dividends. Former Secretary of Nepal Government, Krishnahari Baskota, says, “The company was ruined due to political interference. Political appointments, trade union issues, and incompetent staff recruited by political parties led to the company’s inability to adapt its production to market competition, resulting in its closure.”

As the company began to incur losses, the government kept increasing its investment, leading to a total of Rs. 1.03 billion in government shares in the industry.

Similarly, businessman Ramesh Wagle holds shares in Jyoti Spinning Mills. However, he discovered that the company had been liquidated without sharing any dividends. He also hasn’t received the principal amount he invested in the company’s shares.

Ratnasagar Shrestha, the head of the financial division of the Jyoti Group, which promoted the company, said that after the decision to close the company, an announcement was made for investors to come and collect their refunds. However, he did not disclose the exact date of the notice, the duration of the announcement, or how many were refunded. “I don’t know about these events which happened 20-25 years ago; I’m busy now,” he retorted.

Dinesh Bajracharya, who previously worked for Jyoti Mills and is currently employed at Syakar Company, also under the Jyoti Group, claimed that the company has been refunding the investment amounts to those who bring in share certificates. However, he did not provide details on where to go or whom to meet to receive the refund.

Delisting Debacles

In addition to the above companies, another 53 companies listed on the Nepal Stock Exchange (Nepse) have also vanished, taking public investments with them. Most of the companies listed on the stock exchange before the Securities Act 2063 came into effect no longer exist. Others still exist legally but have no traceable operations or assets. Companies like Nekon Air, Bansbari Leather Shoes, Birat Shoe, and Arun Vegetable Ghee Industries were once established in the market but are now closed. Investors in 56 companies, including Morang Sugar Mills, Biratnagar Jute Mills, and Shriram Sugar Mills, have not only failed to receive any dividends but have also lost their principal investments.

Detailed records of companies such as Nepal Med Limited, S. Laboratories (Nepal) Limited, Basbari Leathers Limited, Kathmandu Bread Industry, Pokhara Bread Industry, Hetauda Leather Industry Ltd., Indreni Soyabean Ltd., Everest Wool Industry, Agro Nepal, Himgiri Textile, E.L.S. Laboratories, Pokhara Bread Industry, Nepal Trade and Temple Ltd., and others are not available with the Nepal Securities Board or the Nepal Stock Exchange. Many of the share certificates that Damruballabh Ghimire had piled on his table belong to such defunct companies, where the general public’s investments have been lost.

The certificate showing procured shares of Gorakhkali Rubber Industry

In 2047-48 BS, the government had created provisions for a 10% tax exemption for any company listed on the Nepal Stock Exchange that issued an IPO. But former Finance Secretary Krishnahari Baskota has accused the private sector of misusing investors’ funds by issuing shares to a limited number of people to take advantage of this tax exemption. “Initially, the companies would raise money by selling shares, get the tax exemption, then manipulate the share prices, buy back the shares themselves, or shut down the company after raising investments,” he says. Baskota cites Nepal Metal Company as an example of how some promoters who issued IPOs manipulated the market to shut down the company.

According to Nepal Stock Exchange (Nepse), when Nepal Metal Company was established in 2033 BS, its paid-up capital was Rs. 9 crore. Of this, the government held 42.34%, the Khetan Group 27.57%, a Chinese company 26.17%, various government institutions 2.19%, and the general public 1.77%.

When the company needed additional capital to mine zinc and lead, the government increased its capital and raised its share percentage to 71.31%. The company’s accountant, Hari Prasad Ghimire, informed that the company’s paid-up capital reached Rs. 10 arab after the government’s additional investment, reducing the Khetan Group’s stake to 13.50%.

Subsequently, the Khetan Group filed a case against the capital increase in the Appellate Court in 2063 BS, but the court ruled in favor of the Nepal Metal Company. The Khetan Group then appealed to the Supreme Court in 2075 BS, but the Supreme Court also ruled in favor of Nepal Metal Company on Shrawan 10.

According to Ghimire, the government will decide how to operate the company only after receiving the full text of the Supreme Court’s verdict.

Investors like Damruballabh Ghimire and Ramesh Wagle accuse business operators of deliberately showing losses in companies to benefit themselves, leaving ordinary investors without dividends and eventually leading the companies to collapse. Ghimire claims, “Nekon Air started incurring losses in its second fiscal year after going public, mainly due to corruption by the directors when purchasing aircraft parts and other operational equipment.”

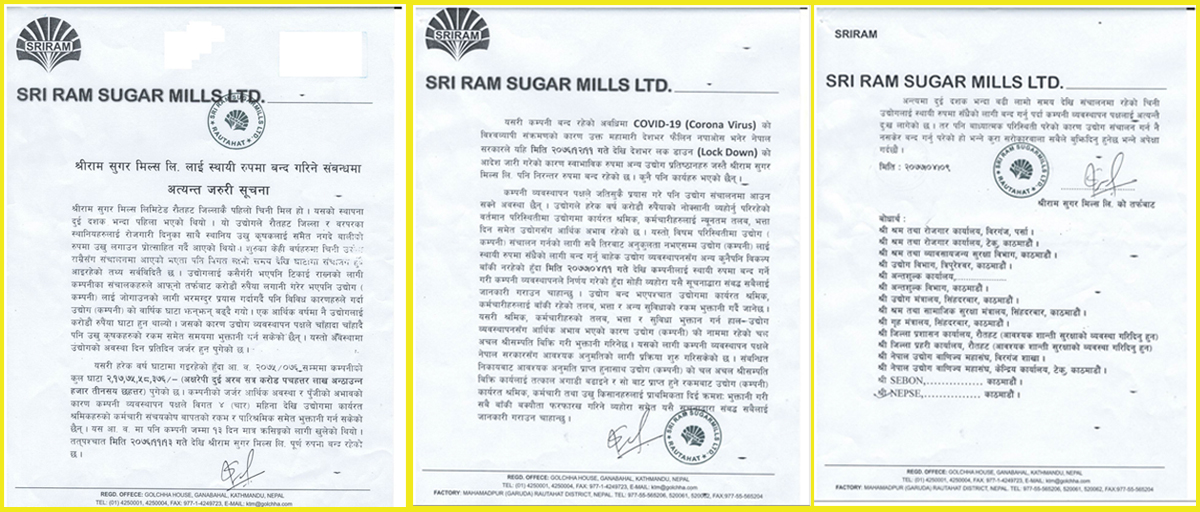

Another company that has sunk public investments and closed down is Shriram Sugar Mills. On Shrawan 9, 2077 BS, Shriram Sugar Mills announced its complete closure, citing losses of Rs 2 arab 17 crore 75 lakhs billion. The announcement stated that the company’s assets would be sold off to pay the remaining wages of the employees. However, after evaluating the company’s liabilities and assets, the remaining amount has not been distributed to general investors. The trading of shares in this company has been suspended for 16 years.

Golchha Organization alone has promoted four companies—Shriram Sugar Mills, Biratnagar Jute Mills, Raghupati Jute Mills, and Arun Vegetable Ghee Industries. Despite raising funds from the public, these companies neither paid dividends nor returned the principal investment to shareholders. Ghimire says, “All the companies the organization runs solely with their own investments are doing well, but once they take public investments, the company supposedly starts losing money and the business closes down taking the public’s investment with them.”

New Faces, Old Risks

This trend of leaving investors high and dry after issuing IPOs continues to this day. Recently, some companies that have raised funds from the public by issuing IPOs are showing signs of repeating history. The lack of strong regulation and corporate governance, means that the risk of ordinary investors being cheated continues to exist.

Nepal Republic Media Limited, the publisher of the newspaper Nagarik Daily, for example, raised Rs. 35 crore 25 lakhs through an IPO last year. Before issuing the IPO, the media company claimed that its earnings per share (EPS) would be Rs 7 and 22 paisa until the end of Chaitra 2079 (March-April 2023). However, just three months after selling its IPO, the EPS dropped to Rs 0.14 by Asar 2080 (June-July 2023). When the company issued its IPO, it had projected an EPS of Rs 5 and 55 paisa for the fiscal year 2080/81. By Chaitra 2080, the EPS turned negative to Rs. 0.54 per share. This shows that the media company misled the public with incorrect projections and data to sell its shares. There are many other similar companies that present attractive financial statements and deceive the public by selling shares at premium prices.

In Ashoj 2080 (September-October 2023), Sonapur Minerals & Oil Limited issued primary shares at Rs. 225 per share and collected Rs. 2 arab 18 crore and 98 lakhs. The company had shown an EPS of Rs. 7.8 in the fiscal year 2079/80 and promised future profits. However, after selling the shares at a high price, it is now found that the company is operating at a loss, and its EPS has turned negative. The company’s EPS, which was expected to reach Rs. 17.58 by Asar 2081, had actually fallen to a loss of Rs. 9.04 by Chaitra 2080. Despite claiming a net worth of Rs. 201.65 per share, the shares were only Rs. 170.73 by Chaitra. This indicates that Sonapur, a company associated with the Tayal Group with Ratanlal Tayal serving as the chairman, misled investors with incorrect information to encourage them to invest in the company’s shares.

Furthermore, some companies like Himalayan Reinsurance have even lobbied regulatory bodies to amend existing laws in order to raise funds from the public. Initially, the company proposed to invest Rs. 7 arab from the founders and raise the remaining Rs. 3 arab from the public out of a total paid-up capital of Rs. 10 arab. However, the founders influenced state mechanisms to amend the ‘Securities Registration and Issuance Regulations, 2073’, and issued primary shares at a price of Rs. 206 per share. This allowed the company to collect Rs. 6.18 arab from the public, more than double of what was initially laid out. The rule requiring a company to be profitable for three consecutive years to issue shares at a premium was also amended to two years to facilitate this company. Himalayan Reinsurance, chaired by Shekhar Golchha, also includes other well-known investors like Kailash Sirohiya of Kantipur Publications, former president of the Federation of Nepalese Chambers of Commerce and Industry, Pashupati Murarka, Sahil Agrawal of the Shankar Group, and businessman Deepak Bhatt.

Share market analyst Mukti Aryal states, “Influential business houses manipulate the system to issue IPOs at premium prices. This leads to ordinary people getting trapped while the operators benefit.” Former Executive Director of Nepal Securities Board, Niraj Giri, claims that recently, companies have been using loopholes to raise as much money as possible under the guise of IPOs. Aryal also accuses influential business groups and elites of raising money as they please through IPOs by manipulating the Securities Board. He says, “People with political influence are changing policies and exploiting legal loopholes to harm the general public.” Aryal further states that if a company provides false information after issuing an IPO, the operators and the certifying chartered accountants should be punished.

The legal mechanism for share distribution

According to Section 97 of the Securities Act, 2063, providing misleading information to the public is considered an offense, with penalties ranging from a fine of Rs. 1 lakh to Rs. 3 lakhs or imprisonment for up to two years, or both. However, the Securities Board remains silent even when the information presented in the prospectus differs significantly from reality. Market analyst Aryal argues that the penalties and imprisonment periods mentioned in Section 97 are too low, encouraging companies to defraud the public. He says, “Even if arabs of Rupees are defrauded through an IPO, the fine is only Rs. 3 lakhs, so it’s necessary to increase the fine and imprisonment duration.”

Dr. Navaraj Adhikari, spokesperson for the regulatory Nepal Securities Board, explains that the board approves IPOs because all details are certified by chartered accountants and the responsibility of the shares lies with the underwriter. However, the Securities Act, 2063, also provides the board authority to compensate the public for any losses caused by company fraudulence, but power is yet to be exercised. Nor has the board ever recommended that any chartered accountant be punished by the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Nepal (ICAN) for financial misrepresentation.

Former Executive Director of the Securities Board, Niraj Giri, says that due to the influence of the Ministry of Finance and large business houses, the Securities Board cannot function professionally. Moreover, current legal provisions allow any company to issue IPOs without much trouble, according to experts.

According to Directive No. 30 of the Securities Issuance and Distribution Directive, 2074, IPOs must be distributed at a minimum of 10 shares per applicant. This provision makes it easier for small investors to buy at least 10 shares and sell them at double the price in the secondary market, leading to the over-subscription of any IPO, explains market analyst Jyoti Dahal. He adds, “The possibility of selling in the secondary market at double the price leads to the over-subscription of any IPO, allowing promoters to collect as much money as they want.” Dahal suggests that setting a separate allocation rule, along with the provision that allows applying for up to 5% of the amount issued for the IPO, could reduce such manipulation.

No Dividends, High Prices

Out of 248 companies listed on the NEPSE, 73 companies have not distributed dividends to investors yet. Despite this, their average price per share is Rs. 557. “Before investing, the financial health and returns of the company are studied,” says Adarsh Bajgain, DGM of Nabil Bank, “But why is investment happening in companies that do not give returns? I have never understood this.” Among the 73 companies yet to distribute dividends (see table), most are promoted by large business houses. “Since they don’t have to pay dividends or interest, large business houses are focused on raising money through IPOs,” comments market analyst Aryal.

Companies that have not distributed dividends so far include well-known companies such as Chandragiri Hills, promoted by IME Group; Panchakanya Mai Hydropower Limited, promoted by Panchakanya Group; Modi Energy Limited, associated with Pashupati Murarka; City Hotel Ltd., associated with Golyan Group; Green Venture Limited, associated with Shanghai Group; and Himalayan Life Insurance, associated with Shankar Group.

The notice released by Shree Ram Sugar Mills

Madhav Prasad Koirala, former Executive Director of Chilime Hydropower, mentions that directors and founders in hydropower companies are engaging in the practice of inflating bills under the name of purchasing various items, selling their shares after three years, and misusing public funds. He explains that due to this, certain individuals gain invisible benefits while ordinary shareholders are left empty-handed.

According to the Securities Registration and Issuance Regulations, 2073, the founder shareholders of any hydropower company can sell their shares three years after the IPO. Koirala, however, points to the fact that founders are taking advantage of this provision by pulling out their investments after three years and leaving the company in disarray. Former Executive Director Giri also argues that hydropower founders should not be allowed to exit right after the stipulated three years.

Furthermore, Nepal Securities Board’s lax approval of IPOs for any company is putting public investments at risk. Currently, some investment companies, hospitals, warehouses, and trading companies are also issuing IPOs. Giri says that the board’s failure to regulate these companies properly is causing significant risk in the market. A high-ranking official at the Nepal Stock Exchange, who requested anonymity, says, “What can happen with a trading company? It makes a profit from the margin on buying and selling goods. If it incurs a loss, the directors will simply leave the company. Why did the board allow such companies to issue IPOs? I have never understood this.”

Another example of a company allowed to raise funds without considering its condition and financial status is Emerging Nepal. The Nepal Securities Board granted Emerging Nepal permission to issue an IPO on 9th Magh 2078 (January 23, 2022) while Under-Secretary Shobhakant Paudel of the Ministry of Finance was acting as chairman. Paudel himself was a member of the board of directors of the company as it had government investment. However, as chairman of the regulatory body, he granted permission for Emerging Nepal to issue an IPO. According to a high-ranking official at the Securities Board, the company was being run by just one employee. He asks, “How can we guarantee that such a company will protect investors’ interests?” The official further reveals that permission for the IPO was granted under extreme pressure from the then Minister of Finance and the board’s chairman. Emerging Nepal, which claims to facilitate public-private partnership projects, has minimal government investment (less than 0.5%). After Emerging Nepal received permission, the Securities Board has not been able to prevent other similar companies from issuing IPOs of their own.

Former Chairman of the Nepal Securities Board, Rewat Bahadur Karki, amended Rule 9 of the Securities Registration and Issuance Regulations, 2073 to allow companies in the real sector to issue a minimum of 10% to a maximum of 49% of their shares to the public, after companies in the real sector did not enter the secondary market. Previously, the provision required a minimum of 30% of shares to be issued. With the new provision allowing the issuance of only 10% of shares, the rule has been misused, opening a path for companies to deceive the public and raise funds. This is because, under this system, the previous requirement of having at least three directors from the public has been changed to just one director. Additionally, with fewer shares available in the market, there is also an opportunity to manipulate and inflate the share price. And companies are already taking undue advantage of this new system. A prominent example is Chandragiri Hills Limited. This company has issued only 10% of the shares for the public, resulting in all but one of its directors being from the IME Group.

Share market analyst Aryal points out that the responsibility of protecting public investments lies with the Securities Board, and the board should act as a watchdog. He says, “If there are doubts about the financial statements presented by any company, the board should re-evaluate them. The undue influence of companies should not overshadow the regulator’s duty to oversight.”