Nepal’s political parties floated a lot of dreams in their local-level election manifestos to lure voters; five years on, those dreams are limited to just dreams. Parties, who made promises that remain unfulfilled, have made a mockery out of important document like an election manifesto, and have gotten a chance to trick voters again and again.

Ramesh Kumar |CIJ, Nepal

“Clean water flow in rivers like Bagmati, Bishnumati, Manohara and Hanumante will be ensured by streamlining water from at least 20 lakes, both natural and constructed, inside the Kathmandu Valley and from rivers outside the valley with the use of lift system. The drainage water in all cities will be purified and put to use for industrial purposes and then be repurified and left to flow into waters, ponds and lakes.”

This is one of many promises that made up the election manifesto of Communist Party of Nepal (United Marxist-Leninist), released ahead of the 2017 local level elections. Let us forget, for once, the “vapid declarations” made by Bidya Sundar Shakya, before and after his election as Mayor of Kathmandu Metropolitan City, the country’s largest. Still this promise from the CPN (UML) is significant because the party led the local government at KMC after the election. The then Communist Party of Nepal, formed after the merger of the UML and CPN (Maoist), ruled the country for nearly three and a half years.

Looking back at that manifesto, it seems that it is making a mockery of itself. Let alone the prospect of clean water in Kathmandu’s rivers, solution to manage garbage disposed by households is yet to be found.

But it’s not only about the UML. Manifestos released by other major parties are nearly identical. These manifestos released by the UML and Nepali Congress and the Maoists’ “Letter of Commitment” had promises that were not just outside of the capacity of local government but were downright fantasies.

With these promises, the UML, Congress and Maoists won 666 of total 753 local unit chief positions up for grabs. Even though the commitments made in manifestos have no legal basis, they are meaningful in a political system that values responsibility and accountability. But looking back at the last five years, political parties have treated limited them to papers only. How major political parties turned their manifestos into worthless documents? In this report, we are exploring just that.

UML’s declaration: tall promises, poor implementation

“Basis of a prosperous, equitable and strong nation: An UML government from villages to the centre”—so went the UML’s main slogan for the local level elections 2017. And like stated in the slogan, voters did indeed give the party an edge. The UML alone won 39 percent of 753 local units, and the Nepal Communist Party, formed after merger of UML and Maoists, led the government in six of seven provinces for nearly three and a half years. The party was in a favorable position to fulfil the commitments of its manifesto. But let alone fulfil, the party couldn’t even scratch the corners of its commitments.

Through its manifesto, the UML had publicized its aim to upgrade Nepal to a middle-income country with a per capita income of $5000 within 10 years. Has anything as such happened though? Let’s take a look at the statistics. According to the Central Bureau of Statistics, in October 2017, Nepal’s PCI was $1900. In October 2022, the figure has reached an estimated $1191. Or, even though the UML led 39 percent of local units and the federal government, the PCI increased an average of $45.5. If Nepal’s PCI is to reach $5000 as UML aimed, it should increase an average of $635 per year, which is itself an impossible aim. Because in the last ten years, Nepal’s PCI has increased only $383, an average of $38 per year. Now, even if the PCI growth of last ten years takes place in a single year, it won’t reach the aspired $5000.

In its manifesto, the UML had included the aims to produce an additional 15000MW electricity in 10 years and advance a parallel 765KV transmission line of Karnali Chisapani Multipurpose Project along the East-West Highway. In the five years, however, only 194MW electricity has been produced additionally. The production capacity of the project, which was 961MW in March 2018, has now reached 2055MW. Currently projects totaling 3000MW are under construction while other projects with total capacity of 900MW are slated to go into production after agreement with Nepal Electricity Authority. Even if all these projects get completed in five years, the total capacity will reach only about 7000MW.

The UML’s declaration stated an expansion and upgradation of all highways within five years using modern technology. But sections of highways such as Kathmandu-Mugling section, Narayangarh-Buwal, and Pasang Lhamu Highway are decrepit as ever before. The Kathmandu-Tarai fast track, which the UML said it would complete within five years, has only one-fifth of its work complete, while work at the most difficult bridges with three tunnels is yet to be started.

Until mid-January, the 1792KM Postal Highway, which the UML said would be well-facilitated with modern technology, has only 795KMs of it black-topped while 118 of 219 bridges are yet to be constructed. The UML had committed to upgrade the Mid-hill Pushpa Lal Highway to four lanes within five years. Until mid-January, only 1147 Kms of its total 1879 is blacktopped. Forty-six of 137 bridges are yet to be constructed. Many other commitments such as upgrading highways connecting north-south to four lanes among other infrastructure work are limited to papers.

During the elections, the UML drew everyone’s attention by showing dreams of trains running across the country—purported railways include East-West and Mid-Hill Railway, Rasuwagadhi-Kathmandu-Pokhara-Lumbini Railway, Kathmandu-Birgunj Railway. But only one detailed study has been done so far, that of the East-West.

Further, the UML had declared the construction of a parallel tram and ultra-modern metro railway in Kathmandu’s inner ring road. Kathmandu’s Mayor Bidya Sundar Shakya, an UML leader, had declared the operation of metros and monorails. Of the vapid promises made by himself and his party, Shakya says, “Because the ring road isn’t expanded, the monorail project couldn’t take off.”

Among other declarations of the UML manifesto are the ultra-modern international airport in Nijgadh, and other airports in Bhairahawa, promised to be operated within two years, and in Pokhara, in three years. Whether to construct Nijgadh airport is an issue that remains to be concluded. Construction of Bhairahawa airport is just complete and that of Pokhara is yet to be completed.

“Within two years, Nepal will be independent in basic food supplies, and within five years, the country will reach a position where it would export food,” so went another of UML’s commitment. In reality, in the fiscal year 2073/74, Nepal imported Rs 40 billion 150 million worth of food supplies, whereas the import ballooned to Rs 79 billion 590 million in fiscal 2077/78. Since last August to March this year, the import has reached a total worth of Rs 56 billion 930 million. These statistics show the vertiginous rise of the country’s dependence on food supplies.

Even though UML manifesto declared advance in research and construction of diversion irrigation projects such as Karnali-Pandun-Golatitar, Naumure-Shivapur, Kaligandaki-Tinau, Trishuli-Chitwan, Meghauli-Parsa-Belauwa, and Tamor-Morang, to enhance agricultural production, no work has been done yet. The manifesto further committed to establish a Uranium mining and purification center in Mustang, research for petroleum in areas including Dailekh, and iron mine in Nawalparasi, the projects are yet to have detailed study.

The manifesto included establishment of a minimum of one industrial village in each local unit, but the work is not done even in the areas where UML itself won.

UML’s another promise was to make available 50 percent of revenue for infrastructure development in provincial and local level in coordination with finance commission within five years. But for provinces and local units only 29 percent of total revenue trickles down as donation. The party is “committed to make local units stronger, able, independent and empowered,” so was the UML’s another declaration in its manifesto. But while federalism is yet to be strengthened, UML chair Oli remarked in public that the province and local units are not sovereign, but only parts of the center in an April 2021 speech.

Furthermore, the UML’s manifesto aspired to integrate settlements scattered across each ward within five years by formulating a masterplan; develop sub-metropolises and integrated villages; ensure education, health, housing, employment, sports, recreation, and enough drinking water in all citizens at the local level by constructing infrastructure. Even though there has been some improvement in drinking water, education and health sectors, the local units haven’t done anything related to employment opportunities, among other things. The squalid situation of moving electricity and telephone cables, gas and drinking water pipes underground is apparent in Kathmandu.

Other commitments that have proved to be mere mediums to trick voters include construction of “modern and prosperous smart city” in places such as Marsyangdi valley, Ilam, Arun valley, Daman, Waling, Lumbini, Jumla, and Dadheldhura, a “cinema city” in Dolakha, declaration of nine more new metropolises, construction of modern cities in ten places each in Postal Highway and Pushpa Lal Mid-Hill Highway, and development of ten ultra-modern satellite cities.

In its manifesto, the UML didn’t leave out the promises of creating an eco-friendly Kathmandu city, rid it of pollution, garbage mismanagement, dust and pothole situation, and address scarcity of electricity and water. But the current state of the city, where garbage goes uncollected for weeks, appears to be mocking the commitments. According to IQ Air, Kathmandu is today the sixth most polluted city in the world, and Nepal the tenth most polluted country. The situation of drinking water, drainage and roads is poor to say the least. Other commitments such as construction of multi-story buildings for parking, transposing all sorts of factories, brick kilns and workshops outside the valley, constructing three ring roads—inner, outer and extensive–in the Capital are also limited to paper.

Other commitments include ensuring ‘one home: one employment’ scheme withing three years, and formulation of a methodology to provide employment to every citizen over 18 within 10 years. These commitments stand as bitter irony given the face that a 1000 Nepalis leave for foreign employment every day.

Bishnu Rijal, deputy chair of UML’s publicity department, however, claims that there has been “satisfactory work” to achieve the aims in longer term. He says that since the manifesto reflects the party’s ambition, it is important to see whether it has walked the talk. He says, “The manifesto reflects the party’s ambition and short-term and long-term goals. There’s been satisfactory work to achieve long-term goals.”

Congress’s deception

In 2017 election, Nepali Congress won 266 local units, nearabout the UML’s score. Since it released its election manifesto, Congress has been at the helm of the federal government for 17 months.

The Congress had declared to make Nepal a middle-income country with double-digit economic growth within a decade, invite at least Rs100 billion in foreign investment, create employment opportunities worth Rs 300 thousand to 500 thousand per year, and upgrade most Nepalis to middle-class status. But in five years hence, these commitments were limited to imagination only.

Congress had declared the construction of a Kathmandu-Madhes fast track, 1000KM four-six lane road, 500KM railway line, 50,000KM blacktopped road and tunnel network. The work at fast track and expansion of east west highway is ongoing in snail’s pace.

In between this, the three-tiers of government have blacktopped only 21000KM road. According to economy survey 2077/78, the total length of railway inside the country is 56KM. Even though work to construct a tunnel in Nagdhunga and Siddhababa has started, it is not complete as the party had claimed. Nor does it look like the projects would be complete anytime soon.

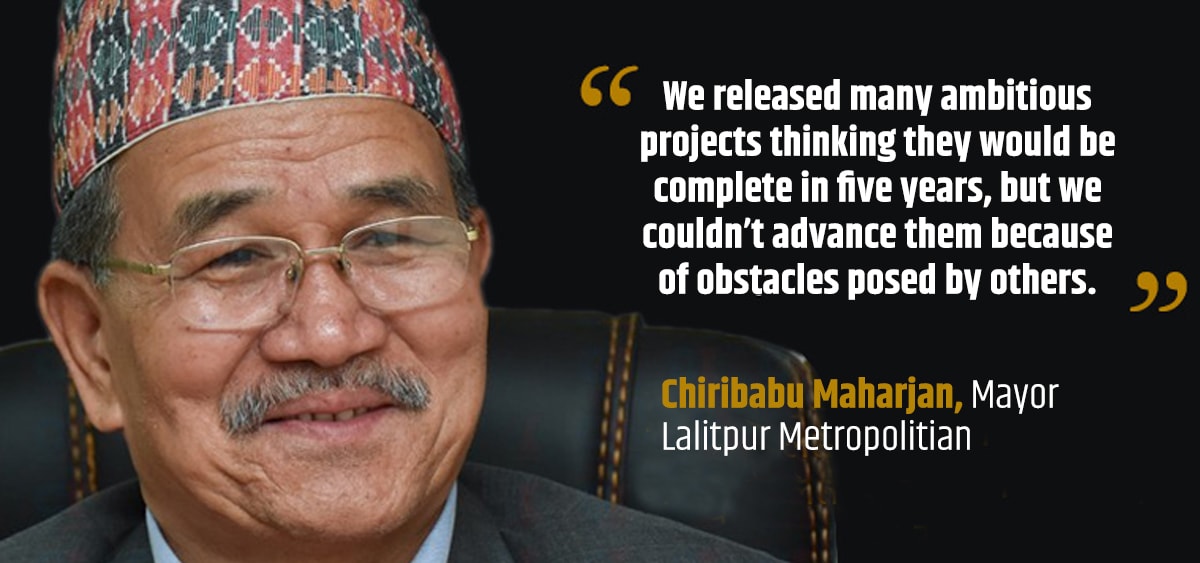

Not just tunnel network, there were other commitments such as construction of flyovers, sky bridges, and monorail network to curb traffic jams and manage crowd. Chiribabu Maharjan, elected through Congress quota as Lalitpur mayor, declared construction of a flyover linking Thapathali to Pulchowk. But these have remained declarations only.

Congress also declared operation of four international airports, irrigation projects to benefit 1.8 million hectares in Tarai and hills round the year, but these too are limited to the papers.

The party had committed to address the dreadful situation of unemployment in the country by collaborating with local government: “To develop extensive skill development opportunities and promote technical education to create employment, and formulate a policy to provide educated unemployment allowance to those engaged in communal service and development works.” Even though Congress announced it would introduce schemes such as ‘one family one employment’, and ‘youth’s goal – skill and capacity’, the local units led by the party didn’t put much effort to create employment. The fact that as many as 200000 youth took labor permit to go for foreign employment between July and February tells how pervasive a problem unemployment has become in the country.

Further, Congress had declared to implement various projects such as ‘Yuwa Uddham Chunauti Kosh’, Remit Hydro, Remit Infrastructure, Remit Housing, etc, to promote self-employment among youths. But these declarations, too, became only the ploys to trick voters.

The manifesto had mention of global democratic methods such as providing easy access to loan for farmers and entrepreneurs, founding of farmers’ clubs, opening bank accounts for everyone over 16, creating a responsible local government by monitoring public expenses and using citizen report card. But these declarations didn’t get implemented even in local units where Congress itself won. Other commitments that went to waste are easing primary education to infants from middle-class backgrounds under the one tole-one infant development centre scheme, and encouraging mothers with cash to continue to educate their children.

Moreover, there was also mention of good-governance measures, such as creating a skilled, responsible, impactful bureaucracy free of corruption, which the party deemed as its primary policy. But the fact that cabinet ministers, including PM and Congress president Sher Bahadur Deuba himself, didn’t release their property details until nine months of appointment made a mockery of this policy. While the erstwhile government led by KP Oli had released the property details of all ministers shortly after appointment. Congress, which aimed to embrace policy of zero tolerance against corruption and economic crimes, is now embroiled in many corruption scandals.

The party had declared to establish a 15-bed hospital with pregnancy facility in local units it led, construct blacktopped roads to connect wards and toles, taps in each home, latrine and waste management, an integrated home for elderly, disabled-friendly public infrastructure, integrated service for agriculture, animal husbandry, drinking water, irrigation, tourism, trade and industries, and services of fire extinguisher and ambulance. But the local units that have worked towards that are few. Congress spokesperson Dr Prakash Sharan Mahat says that since it was the first local level elections, many of the proposes are of the nature to be carried out by the central government. He says, “We didn’t lead the government in center and provinces. And even though we now lead the central government, we haven’t been able to pass budget incorporating our concerns and priorities. That’s why the commitments didn’t get carried out. The upcoming budget will prioritize the implementation of programs that we’ve declared.”

The Maoist party worsens further

CPN (Maoist Center) in its commitment paper targeting the local elections showed dreams of mobilizing labor force through a labor bank, create employment by forming youth self-employment and poverty alleviation fund, and provide employment allowance until productive employment is ensured. But the fact that these commitments didn’t get implemented in the local units it won shows the hypocrisy of the Maoist party. There were other plans that didn’t get properly implemented such as constructing health posts in each ward with skilled manpower, ensuring sanitation and clean drinking water in every village, providing allowance to new mothers, single women and pension to elderlies over 60, forming infant care center in each ward, installing free wifi service in each village, etc.

The commitment paper also includes plans to control black marketing, inflation, and artificial scarcity, and managing market that focuses on consumer rights. These declarations should have been thoroughly carried out given that a Maoist head the federal ministry of finance today. But the reality is that, inflation, that was normal for six years, is on the rise since July this year. Families are troubled due to price hike in everyday goods.

Smart model village, one village one model industry, easy access to drinking water in urban areas, management of garbage, addressing mismanaged housing and squatter settlement, construction of metro line, and electrifying public transportation were other Maoist commitments that remain unfulfilled. The Maoist party led 106 of 753 local units but it couldn’t make good on its commitments. Maoist leader Dev Gurung says that since the party was not leading the federal and provincial government, it couldn’t do work as aspired. He says, “We couldn’t do work as we desired even in local units we lead because the federal and provincial government didn’t provide budget and human resource.”

The case of the metropolis

When he was vying for the Mayor of Kathmandu, Bidya Sundar Shakya announced a ‘101 works in 100 days’ campaign, which included a metro rail service in three years, public transportation for 20 hours, a clean smart city, cycle city with no traffic jam. Of course, none of these promises get fulfilled. Of the inability to construct metro rail, Shakya says it was due to “inability to expand the ring road.”

The Kathmandu Metropolis didn’t do anything in five years to improve public transportation. There are potholes galore in the dusty streets and chowks. The metropolis’s aim to construct toilets remains unfulfilled.

A road network without jam, management of electricity poles and cables, Hello Mayor Quick Response program, Kathmandu Smart Citizen car, a lively city running for all 24 hours, and ‘a people without hunger, metropolis without sorrow’ program—these are other programs that are limited to papers. Mayor Shakya courted controversy for his negligence in heritage construction, and in incorporating Nepal Bhasa curriculum in schools.

While Chiribabu Maharjan, Mayor of Lalipur and an NC leader, didn’t prove to be as controversial as his neighbouring counterpart, his plan to construct a flyover from Pulchowk to Thapathali, cleaning the capital with Melamchi’s water twice a week, metro rail and construct of tourism ring road, and water canal proved to be only measures to lure voters. Other commitments that remained on paper are financial help to poor and bonafide students, creating a cultural capital city, reestablishing stone spouts, and establishing a library in each wards, a Ayurveda hospital and Yoga and Physical centre. In creating a designated cycle lane, installing smart lamps in the city and reestablishing heritage, however, Maharjan won praises.

Pokhara Mayor Man Bahadur GC, an UML leader, appeared a step ahead in tricking voters. He announced projects such as smart metropolis, Kerung-Kathmandu-Pokhara-Lumbini railway that would establish Pokhara as a major commercial-tourism hub, cycle lane, flyover, and metro rail with tunnel, integrated communal housing and one house to each squatter household. His other announcements that didn’t get carried out include a elderly citizen club in each tole, well-facilitated infant centre, employment to youth and guarantee of social security, smart card for easy service delivery, loan to small entrepreneurs without collateral, employment opportunities in agriculture sector for foreign returnees, subsidized agriculture loan, and allowance to unemployed.

Renu Dahal, Bharatpur Mayor, announced to establish the city as an alternative capital city, a metro and monorail service, construction of inner and outer ring road, flyovers, underground road construction. Her other commitments include free technical education to marginalized children, a city without electricity cables, managed bus park, a garbage treatment plan using modern technology, wifi-free zones, cable car operation, free medicine to elderlies to 70, and subsidized loan to entrepreneurs.

Bijaya Saravagi, Birgunj Mayor who comes from a business background, committed to make a ‘quality city’ by ending unemployment, construct roads and schools, and electricity and banking infrastructure. His other unfulfilled commitments include construction of a satellite city, a ring road, a city without mosquitoes and germs, and irrigation facilities.

Saravagi, who has millions of fortunes, announced that he wouldn’t ride the government’s vehicle. But he couldn’t make good on this promise. Now he travels in well-facilitated car belonging to the metro city. In the meantime, he has changed parties, from Samajbadi, with which he got elected, to Janata Samajbadi to UML today.

Biratnagar Mayor Bhim Parajuli, a Congress leader, promised to turn the city into an ultra-modern, prosperous one, create employments, construct ring road, revitalize Biratnagar Jute Mill, create energy from waste, operate city bus and affordable shops. His other unfulfilled promises include construction of a cremation centre, and rid the city of dust, dirt and flooding. The Chhath after he got elected, he performed a religious act, by crawling to the Shiva Panchayat temple wearing saffron clothes, for “the city’s prosperity”. Now the city is crawling in snail’s pace just like the mayor did.

This is perhaps the reason why far-flung local units have fared better than the large ones. In the index released by the Natural Resource and Finance Commission assessing the work of local units, they have achieved an average of 56.1 points out of 100. The number of six metros is only 53.72 on average. Pokhara has received the most 59.46 points and Birgunj the least 48.64. Kathmandu and Lalitpur have received 56.17 and 51.41 points respectively. Biratnagar and Bharatpur, 55.57 and 51.08, respectively.

Lalitpur Mayor Maharjan claims he has accomplished 90 percent of work he promised. He argues that all the work was not complete because of lack of improvement in public procurement laws, and incooperation from other local units. “We released many ambitious projects thinking they would be complete in five years, but we couldn’t advance them because of obstacles posed by others.”

Tricking voters, till when?

Election manifestos are documents that include the party’s ideology, aim and plans. People vote based on them. The candidates and parties should declare their plans, priorities and programs through their manifesto. That’s why, in a responsible and accountable democratic system, manifesto are measures in ethical terms. Those who can’t make good on their promise are proven unreliable.

But what about in Nepal? Economist Keshav Acharya says that since ethics and accountability are in short supply in Nepal’s politics, a situation like this has arose. “Even though they don’t fulfil their promise, they won’t get punished and that’s why manifestos big on promises get released. Until the voters ask the parties and candidates about unfulfilled promises, this situation will repeat.”

Achyut Wagle, Kathmandu University professor and a columnist who writes about political economy, says that manifesto get prepared in a random way, so they consist more empty promises than one that could get fulfilled. He said, “Parties should have just prepared a template. Manifestos should have been made by local units looking at their capacities and needs. In absence of that, even Humla’s mayor sowed dreams of a smart city.” He believes that if the voters seek accountability from leaders, this trend would stop and parties that don’t make good on their promises would lose.

Indra Adhikari, a political commentator, says that parties make tall promises because of “over-politicization” that extends to voters too and due to a lack of practice to seek accountability. She says, “There is no practice where people enquire whether the promises made in the past got fulfilled. Each household is connected to some party and there’s no check and balance. People need to examine how much of the promises of manifesto materialized. The people are also at fault for voting without reviewing the parties’ and candidates’ past records.”